‘Tell My Managers I’ll Be Waiting For Them In Hell.’

If you or someone you know is depressed or thinking about suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. Or you can text the Crisis Text Line at 741741. Both are available, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

On February 2, 2019, Transportation Security Officer Robert Henry jumped to his death from the tenth floor of the Hyatt hotel inside Orlando International Airport.

The last line of his suicide note: “Tell my managers I will be waiting for them in Hell. Especially the ones who feel this was necessary.”

An investigation by WMFE has found a pattern of abuse and retaliation at Orlando International Airport and across TSA.

- Multiple TSA agents said Robert Henry was bullied at work, but an official investigation by TSA has not yet been released.

- Robert Henry was trying to leave Orlando International Airport and move back near his family, but couldn’t transfer because he had been written up.

- The death has brought out years of allegations of retaliation among airport workers under former Federal Security Director Jerry Henderson.

- Two officers responding to a WMFE survey have been hospitalized for suicide attempts or thoughts, and said TSA was a major contributing factor.

Security officer Robert Henry jumped to his death inside the airport. Photo courtesy Sylvia Henry

Henderson has been temporarily replaced while TSA investigates Henry’s death.

TSA released a statement that says any incidents of bullying or workplace issues “have been promptly investigated.” TSA officials have started an administrative inquiry after Henry’s death and “has continued to actively investigate personnel concerns raised by our workforce. TSA places a high priority on addressing any workplace and personnel concerns when they are raised.”

But did TSA fail Robert Henry?

“I would say any time we have a situation where an employee feels this lost, that they feel that they have no other choice but to take their life, we have all failed as a society,” said Acting Deputy TSA Administrator Patricia Cogswell in an exclusive interview with WMFE. “I think this is something devastating on a day-to-day basis that hurts his family, that hurts his airport family, that hurts us as an agency.

“I can’t express enough my sadness that this happened,” Cogswell said.

But Robert Henry’s family still has questions about what happened that morning.

'I have resolved to take matters into my own hands' What we know - and don't know - about Robert Henry's death

Robert Henry jumped from the tenth floor of Hyatt inside the airport. Photo by Isaac Babcock

At 9:28 a.m., Robert Henry hit send on an email to family and friends. Three minutes later, he killed himself.

In the email, Henry said he had nodded off at work and it looked like he was about to be fired. He’d recently switched shifts and was having trouble staying awake on the early-morning shift.

Henry, 36, had worked for TSA his entire adult life. He wrote that if he lost his job, he had no other purpose.

“I jist(sic) can’t help making myself a target for management,” Henry wrote. “I will NOT burden my parents with my issues so I have resolved to take matters into my own hands.”

He finished the email: “Tell my managers I will be waiting for them in Hell. Especially the ones who feel this was necessary.”

Henry took the elevator to the tenth floor of the Hyatt International inside the Orlando airport. He climbed up onto the railing overlooking the atrium and fountain.

TSA Supervisor Felicita Alicea heard someone on her radio tell her to look up. She immediately recognized Robert Henry. She had previously been one of his supervisors.

“I was calling out to him, like, ‘Robert, what are you doing,’ like, ‘Robert what’s going on, what are you doing?’And I’m waving my arms to him,” Alicea said. “And he looked down and saw me, put his head back up. He closed his eyes, put his arms outward and he just leaned forward and … dropped.”

LISTEN: Robert Henry’s impact caused a flood of panicky 911 calls. Photo by Isaac Babcock

Robert Henry’s family still has questions about his death. His airport access badge was initially unaccounted for.

They wonder if it was taken from him that morning and that he was fired right before he jumped. And if that’s the case: Why did no one walk Henry out? Why wasn’t a union representative in the room when he was fired?

Deb Hanna is the union officer representing TSA employees at the Orlando airport. Hanna said Robert Henry’s immediate supervisor was not going to write him up for nodding off – but that a different officer went over that supervisor’s head and got managers involved.

Hanna said Robert Henry was brought into a meeting with managers that morning. He was told he was being investigated for falling asleep. That investigation would take weeks or months to conclude, she said.

“They were gonna have to investigate,” Hanna said. “But he was not at that point fired, and everybody is saying that and that’s not true.”

Hanna has seen the paperwork Robert Henry filled out to go home early that morning. Robert Henry told his supervisors he wanted to go home because he had a toothache. And instead of leaving, he walked across the airport and jumped to his death.

Hanna said TSA’s own investigation into Robert Henry’s death concluded that Robert Henry was not bullied. Rather, TSA said employees who say Robert Henry was bullied are disgruntled.

Hanna disagrees with that conclusion.

“I think when you have TSA investigating TSA, you’re not ever gonna get the right answer or an honest answer,” she said. “Because you’ve got the fox watching over the chicken coop.”

According to a public records request filed by WMFE, Robert Henry’s airport access badge wasn’t deactivated until five days after his death. But there is still no official accounting of what happened that morning.

“I would love to see the truth, the whole truth, to come out,” said Sylvia Henry, Robert Henry’s mother. “I would like to see a timeline of what happened to Robert on that morning.”

TSA responded to our interview request as the series went to air. Acting Deputy Administrator Patricia Cogswell confirmed to WMFE that TSA’s investigation concluded Robert Henry was not targeted or bullied by TSA managers. She said lawyers are currently reviewing it for release to the family and the public.

“The report did find he was not specifically targeted by management,” Cogswell said. “However, the report also highlighted where he had been having a number of issues.”

Listen: The full interview with TSA Acting Deputy Administrator Patricia Cogswell

Listen: The full story of the investigation into Robert Henry’s death as heard on air

To His Friends, He Was A Gentle Giant To His Bullies, He Was 'Lurch'

Robert Henry spent several holidays with Brenda Shearer’s family. Photo courtesy Brenda Shearer.

When Sylvia Henry thinks about her son Robert, one of the first things she remembers is his love of Disney movies.

“He loved to sing along with the songs of the Disney movies,” Sylvia said. She remembers Robert singing “Once Upon a Dream” from Sleeping Beauty. “He would sing the whole song.”

His childhood dream of living near Orlando’s theme parks was one of the reasons Robert transferred from Dulles International Airport to Orlando International Airport. He left his family in Virginia trying to become his own man.

But in Orlando, his dream turned into a nightmare.

“Here in Orlando, people behind his back called him Lurch,” said Stan Tuchalski.

Tuchalski was Robert’s supervisor at Dulles and then again in Orlando. He was also Robert’s coworker and friend.

He said Robert took a pay cut and a demotion to come to Orlando.

But Tuchalski said Robert wasn’t prepared for the bullying he would get from managers and other officers.

“I never saw him as a Lurch,” Tuchalski said. “I knew him to be intelligent. I knew him to be someone who dearly loved his parents and enjoyed his brothers.”

Robert and his siblings on a family vacation. Photo courtesy Sylvia Henry

Tuchalski said not enough of Robert’s managers got to know him the way he did. He said Robert could seem quiet and even withdrawn in Orlando.

That’s why he said shortly after Robert arrived at the airport, he started having problems with his coworkers.

“And I think because of that people misread him,” Tuchalski said. “And then people presumed things about him. People ostracized him. And sometimes in the misunderstandings, things developed.”

Brenda Shearer is a retired TSA officer who was like a second mother to Robert Henry. She took him under her wing after she saw him being bullied. She said the bullying took many forms, including being written up for things in excess.

“He could be doing the exact same thing as somebody else, like have their phone out,” Shearer said. “And he would be the one getting written up and somebody else wouldn’t get written up because they were buddy-buddy with a supervisor or manager or lead.”

Robert Henry at the parks with the Shearers. Photo courtesy Brenda Shearer

Shearer, like Stan Tuchalski, said she also observed colleagues making fun of Robert behind his back.

“He walked away from the podium and all of them just started talking, ‘He is the weirdest man I’ve ever met in my entire life. I wouldn’t trust him as far as I could throw him’,” Shearer said.

“And I was standing there and I just looked at everybody and I went, ‘Y’all need to just shut up, I’m done with all of you.’ And I walked away.”

That’s when Shearer started standing up to Robert’s bullies with him. She said Robert and her were a team after that.

“My eyes were opened,” Shearer said. “And I went-you need me. Wherever you are, you find me. I’m there. Don’t worry about it. I got your back.”

When space opened up on her family’s farm in St. Cloud, Shearer invited Robert to come live with her and her two adult sons. She said Robert fit right in with her family. He taught her sons video games, drove them to school, and took them to see Marvel movies.

Robert Henry and his brother at the parks. Photo courtesy Sylvia Henry

“He was so sweet and had a big rip-roaring laugh,” Shearer said “They would sit there at the dining room table and I would be like ‘What are we talking about? Can we talk Star Wars because I at least understand that’.”

But Shearer said this didn’t make the bullying any less hard on Robert. He would tell her about wanting to go home when things got really bad.

“He said ‘They kept moving me around. They kept putting me in places nobody else would go.’ I said- ‘Robert be strong you got this. I’ve got your back. There’s people there that care about you. And we just need to get you out of that airport.”

Shearer said at work, things would follow a pattern with Robert. She remembered a time Robert got a bonus for spotting a bag that shouldn’t have gotten through screening.

“He was the only one and he got a $500 spot award,” she said. “So he would be exceptional and then they would ding him for something.”

Robert Henry on a ride at the parks. Photo courtesy Sylvia Henry

Stan Tuchalski remembers telling Robert he should move back home to Virginia in 2018, a year before he died.

Lawmakers were talking about privatizing the Orlando TSA at the time, and no one was sure if they’d have a job when it was all over.

“Rob was experiencing some difficulty at that time and I remember having a conversation with him in the food court. And saying, ‘You know Rob, Why don’t you go back to Dulles? You thrived in Dulles’.”

But Tuchalski said Robert told him he had just gotten written up again for having his phone out.

That meant Robert would have to wait a year before he could apply for a transfer.

Robert Henry and his parents. Photo courtesy Sylvia Henry

On February 2, Robert sent an email to close friends and family. In it, he said he couldn’t help but make himself a target of management.

He had fallen asleep on the job, a severe offense in the TSA, and had gotten written up.

Stan Tuchalski and Brenda Shearer said in March he would have been able to transfer back home.

“So he knew he was almost done with that paperwork so he would be able to put in a transfer back to his family,” Shearer said. “And then he was going to be written up again. So he felt trapped.”

But all those dreams died with Robert Henry when he jumped from the balcony of the Hyatt Regency Hotel inside the airport.

Robert’s mother Sylvia Henry said he used to call and say he wanted to come home.

“He just wanted to come home and get away from this horrid situation that he found himself in,” Sylvia Henry said.

“It was just a toxic mix. I mean he felt he had no other way to go. He knew he wouldn’t be getting out of there.”

Listen: The full story of who TSO Robert Henry was as heard on air

Not Just A Cry For Help. A Call For Change.

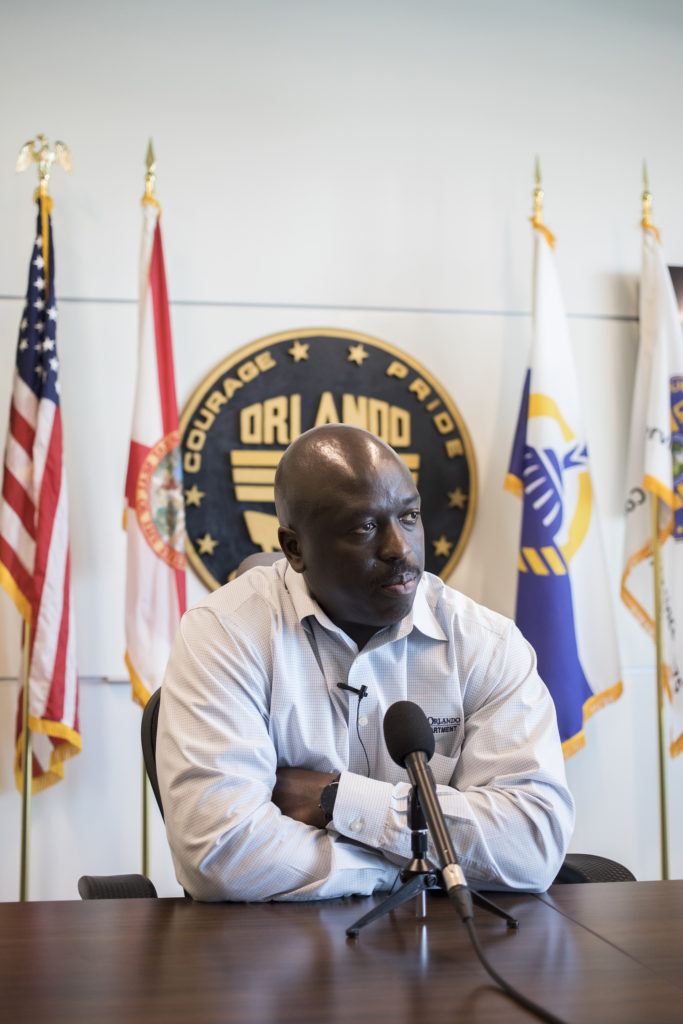

David Platt told investigators looking into Robert Henry’s death that TSA leaders ran the airport using fear and intimidation. Photo by Isaac Babcock

After Robert Henry’s death, TSA officials came to the Orlando International Airport to investigate “multiple allegations of workplace concerns.”

When investigators spoke with bomb specialist Dave Platt, he told them TSA leaders run the airport using fear and intimidation.

Platt said Robert Henry’s death was not just a cry for help, but a call for change.

“Henry is one thing, but what I’m thinking about is all the people that have been fired and the mental anguish that’s been perpetuated on them and how many years or days that’s taken off of their lives of undue stress,” Platt said.

Platt is one of four TSA agents who spoke with WMFE on the record about alleged bullying.

All four have filed legal action against current and former TSA managers in Orlando, and three have been accused of harassment themselves.

Dave Platt said he’s been transferred and suspended because he reported his supervisor for putting an inactive IED on a plane. Photo: Isaac Babcock

Most of these incidents happened under the leadership of Federal Security Director Jerry Henderson.

Henderson, the man in charge of the TSA in Orlando, was temporarily replaced by Pete Garcia after Robert Henry’s death.

And although Platt said things have improved under Garcia, it’s not enough.

Platt said after reporting second-in-command and Deputy Federal Security Director Keith Jeffries for putting an inert improvised explosive device used for training on a plane, he’s been reassigned and transferred multiple times as retaliation.

Dave Platt with the robot he built in the Army. Photo: Isaac Babcock

According to the incident report, the passenger told TSA officers he was a Department of Defense contractor, and the device was a training aid. The device was allowed on the plane, and Jeffries was later cleared by an internal investigation.

That’s because the federal security director was ultimately responsible for that decision, and was acting within regulations at the time when he let the deactivated bomb on the plane.

“I’ve been mortared before. I’m good. I’ve been down this road. I’ve walked the walk. I’ve had to wear the bomb suit and go down there with the disrupter,” Platt said.

“It’s really tough to come to a place where you know you’ve got to look over your shoulder every day.”

Some officers who claim they were targeted by management said they lost their jobs because of it.

Former security officer Joe Donadio says he got in an argument with his manager. Donadio accused his manager of physical assault, but Donadio was ultimately reported to Keith Jeffries as a “threat to himself and the people around him.”

Security officer Joe Donadio said he was fired because of his anxiety. Photo Isaac Babcock

Donadio said he was told he would need to transfer because of the incident, and he took some time off as his mental health started to decline.

“The anxiety got extremely bad at that point because then it was coupled with depression,” Donadio said.

TSA started a fitness-for-duty investigation into Donadio after he was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder.

The agency ultimately fired him, writing that his condition “medically disqualified” him from the job. Donadio said being fired just made his condition worse.

“I’m very, very, very familiar with that dark place that Robert was in,” Donadio said. “I look up right now and say, ‘Robert, I hear you man, I know that place’.”

Joe Donadio now works as a volunteer firefighter at Marion County Fire Rescue. Photo: Isaac Babcock

Even those near the top of the TSA leadership chain at Orlando International Airport weren’t immune to retaliation.

Sean SanRoman was third-in-command and Assistant Federal Security Director of Screening after Jerry Henderson and Keith Jeffries.

He said he was still a target of bullying. He admits it wasn’t that simple, though.

“I want to be very honest with you. I think I’m part of that too,” SanRoman said. “I think I have a responsibility. I think I witnessed certain things that I think I just let by in the idea of go along to get along.

“And I think I regret that tremendously. In fact, I know I do.”

Sean SanRoman says he was fired after his supervisor alleged he acted erratically in a meeting. Photo Isaac Babcock

SanRoman said the retaliation started after he told Jerry Henderson that Keith Jeffries had given a candidate questions ahead of an interview.

A few months later, Henderson accused SanRoman of erratic behavior at a meeting.

The agency ultimately suspended SanRoman’s security clearance because of “disruptive, aggressive and threatening behavior in the workplace” and Henderson put him on administrative leave.

SanRoman is in the security business. No security clearance, no job.

It took SanRoman a year before he got his qualification back and almost two before he was hired at Sanford International Airport in a similar position.

Sean SanRoman now works at the Sanford International Airport. Photo Isaac Babcock

“Who’s going to hire me? I have to report that the rest of my life,” SanRoman said. “Whenever I want another job in security. I’ve got to rehash everything that’s occurred to me.”

WMFE has made repeated attempts to contact Jerry Henderson through TSA, his attorney and calls to his cell phone. At the time of airing, Henderson had not responded to requests for comment.

Top TSA officials also did not make Interim Federal Security Director Pete Garcia available.

In a written statement, TSA said any incidents of bullying have been investigated: “TSA leadership initiated an administrative inquiry immediately after the death of our officer and has continued to actively investigate personnel concerns raised by our workforce.”

TSA officers talk with passengers at Orlando International Airport. Photo Isaac Babcock

But one official did speak with WMFE in an exclusive interview: Keith Jeffries.

“I could have named them for you right off the get go too. Go ahead what are your questions about them?

Jeffries is no longer at Orlando International Airport, but is the Federal Security Director at Los Angeles International Airport.

Jeffries said Platt was frequently accused of being unprofessional. He recommended Platt be fired, but that recommendation was overruled.

He said he offered Joe Donadio a job that accommodated his anxiety, but Donadio didn’t show up for the job.

And Jeffries was already working at Los Angeles International Airport when Sean SanRoman was put on leave.

Passengers lineup outside of a TSA checkpoint at Orlando International Airport. Photo: Isaac Babcock

Keith Jeffries said he hopes his former supervisor Jerry Henderson is exonerated. If not?

“If not, I expect him to be held accountable,” Jeffries said. “He’s the Federal Security Director.”

“If morale is bad at Orlando and you’re the Federal Security Director at Orlando, it starts and stops with you the leader. He knows that’s how I feel.”

Jeffries remembers meeting Robert Henry at Orlando International Airport. He said Henry was a quiet kid.

After Henry’s suicide, Jeffries conducted town hall meetings at LAX to encourage workers who needed help to come forward.

“Will Robert Henry’s death change things in TSA? I think it already has,” Jeffries said. “I think that it puts it in the bull’s-eye of us to be more aware that we’ve got real people with real people challenges or issues. We have to do a better job as leaders of helping them.”

TSA responded to our interview request as the series went to air. Acting Deputy Administrator Patricia Cogswell said after Rob Henry’s suicide, they sent people to investigate his death and to offer counseling to officers. She said TSA is assessing next steps for Orlando International Airport.

She said federal security director Jerry Henderson and second in command Steve Hanson won’t be returning to the airport “in the next 30 days.” When asked whether Keith Jeffries might transfer back to the airport from LAX, she said nothing has been finalized.

“None of the decisions about the future locations, future decisions around Orlando are completely finalized so I’d prefer not to announce them at this time,” Cogswell said.

Listen: The full story of allegations of bullying made by officers in Orlando as heard on air

WMFE Survey Finds Two More TSA Workers Who Attempted Suicide

The problems with TSA are not just limited to Orlando.

WMFE asked TSA workers to come forward and share stories of the workplace. Seventy-nine people from across the country came forward with stories of harassment and bullying, and examples of nepotism, favoritism and misconduct.

Alison Demzon is one of them. She’s a transgender woman working at Denver International Airport. In 2017, a new supervisor began misgendering her over and over again.

“He looks over and goes, ‘Hey Al, why don’t you come over,’ rather than Alison,” she said. “Go grab him from over there. Which him? Al, Alison, that person.”

Then, in October of 2018 a disabled woman in a wheelchair didn’t want Demzon to do her patdown because she was transgender. The situation was resolved, but afterwards, her supervisor pulled her aside and berated her.

“Eventually, with all that building on top of each other, I just couldn’t take it anymore,” Demzon said. “I just fell apart and started crying all over the place and had to be sent home.”

Demzon was hospitalized on suicide watch. She had two previous suicide attempts before working at TSA.

Demzon returned to work after she passed a fitness for duty test two and a half months later. Demzon filed an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaint against TSA in 2018, alleging she was discriminated against because she was transgender. She is far from the only one.

TSA overall had more than 400 EEO complaints filed in 2018. That is the sixth highest percentage of employees filing EEOC claims among government agencies with more than 50,000 employees.

Christine Griggs is the Assistant Administrator for Civil Rights & Liberties, Ombudsman and Traveler Engagement with TSA. She said the number of TSA complaints is down and more are resolved before becoming legal cases.

She said TSA has a very similar number of complaints as Customs and Border Patrol, which also has about 60,000 employees.

“So if you take that 400 number, and you look at all of our employees as a whole, it represents a little bit less than 1 percent of our total population of employees,” she said.

The discrimination complaints are in addition to allegations of misconduct. When the Government Accountability Office studied misconduct cases at TSA from 2014 to 2016, they found more than 45,000 allegations of employee misconduct over three years. That means in an agency with about 60,000 workers, there was an average of one misconduct case for every four employees every year.

Customs and Border Patrol, which had a near-identical number of employees, had less than half the number of cases.

TSA said it’s important to realize these are allegations (although only 6 percent of TSA cases were found to be unsubstantiated or warranted no discipline). The five most common misconduct accusations are time and attendance issues, failing to follow instructions, security failures (like falling asleep on the job), disruptive behavior (like sexual misconduct or fighting) and neglect of duty which leads to loss of property and life.

About half of the accusations were for time and attendance issues. But misconduct can also be criminal, like accepting bribes or being arrested off the job.

TSA and the Department of Homeland Security consistently rank at or near the bottom of employee satisfaction surveys conducted of all federal employees.

There is a well-documented history of retaliation by management against employees and whistleblowers. An oversight committee recommended legislation to give TSA employees more protections in 2018 after concluding a three-year investigation. It found that TSA employees were forced to transfer because they had accused management of security breaches. The TSA settled those cases for $1 million dollars.

At a 2016 committee hearing in the U.S. House, TSA Deputy Administrator Huban Gowadia acknowledged that more than 1,200 TSA employees have had five or more allegations of misconduct.

“We are bringing a lot of this (data) to a centralized location,” Gowadia said. “All the data we now collect we will be able to mine, look for trends, look for opportunities to improve, opportunities to provide remedial training, etc.”

Former Transportation Security Officer Becky also worked at at Denver International Airport. We’re not using her last name because she hopes a successful Equal Employment Opportunity Commission case will let her be able to return to work for the federal government.

Becky has pseudo brain tumors, a rare condition where pockets of spinal fluid build in her brain and cause migraines, temporary loss of hearing and vision, and vomiting. She said taking time off for a spinal tap to relieve pressure kicked off a year of harassment and retaliation.

“Anything I did, they fought back ferociously,” she said. “They were trying to break me down so I would just resign so they wouldn’t have to deal with me anymore.”

She missed months of work without pay and was eventually fired. That sent her down a dark path, and she was hospitalized twice in the next three months for suicide attempts.

She immediately empathized when she heard about Robert Henry’s suicide in Orlando.

“My heart just broke in a million pieces,” she said. “I was there and I could have been him.”

More than a dozen studies nationwide have found links between workplace bullying and suicidal thoughts. Some researchers have gone so far as to suggest that stopping workplace bullying should be used as an intervention to try and reduce suicide.

Hope Tiesman is a researcher at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Her research shows the rate of suicides in the workplace has been steadily rising to an average of five deaths per week.

“The literature that’s out there, and it’s on the lower end of the spectrum for quality, suggests there is a positive association between workplace bullying and suicidal ideation."

“The literature that’s out there, and it’s on the lower end of the spectrum for quality, suggests there is a positive association between workplace bullying and suicidal ideation,” Tiesman said.

Looking to the future, Becky is packing kitchen gadgets into a big amazon box before her home is sold. At the time of our interview, she didn’t know where she was going to live full-time.

But she needs the money from selling her house to pay for her lawyer: $350 an hour.

“So I have to sell my house and find somewhere else to go,” Becky said.

Becky hopes people will hear about her case and decide they should fight too. “Because if everybody is too terrified to take on [TSA] when they have a valid claim, then nothing is ever going to get accomplished.”

Demzon is back working at Denver International. She said there has been some good from her experiences.

She spoke about her experiences during suicide awareness month with her coworkers. Afterwards, she said, ten or more TSA officers came forward and asked for help.

Demzon has a simple message for lawmakers overseeing TSA: Stop playing politics.

“People are dying,” she said. “It’s that simple.

Griggs, the assistant administrator for Civil Rights & Liberties, Ombudsman and Traveler Engagement, said TSA is now rolling out suicide prevention training. She said she was shocked to hear Robert Henry wrote in his suicide note “Tell my managers I’ll be waiting for them in Hell.”

“I mean, it’s heartbreaking,” Griggs said. “It’s really heartbreaking that someone would get to that point in their life and more importantly there wasn’t somewhere along the line that we could have avoided that, that we as a family could have avoided that. So it’s shocking to me.”

Listen: The full interview with Civil Rights & Liberties, Ombudsman and Traveler Engagement Christine Griggs

Listen: The full story of other officers who struggled with suicide as heard on air

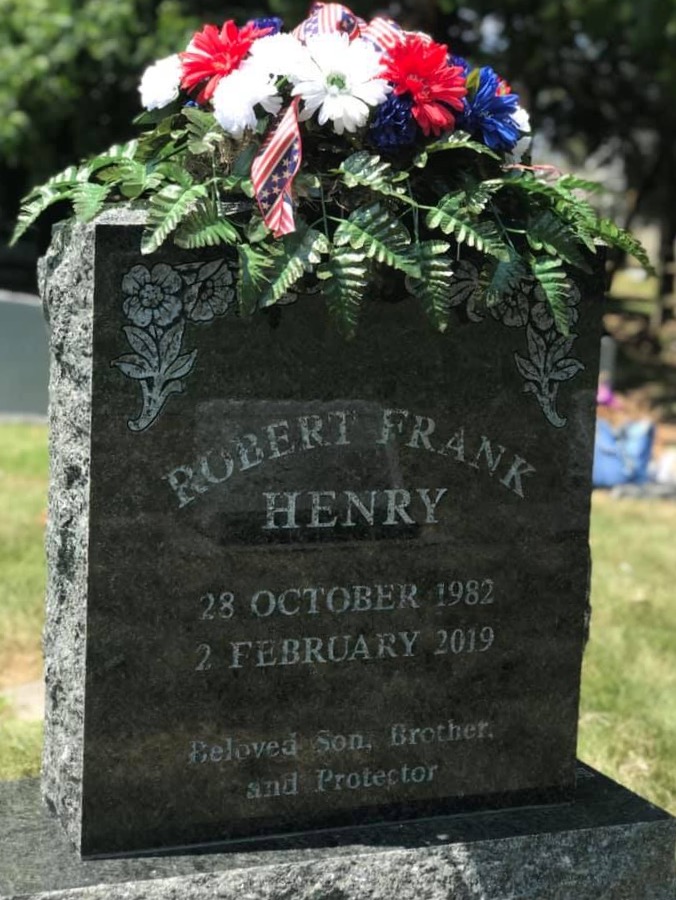

Beloved son, brother and protector.

One of the last times Robert Henry’s mother Sylvia Henry saw her son, they spent time together at the Kennedy Space Center with his father and brothers.

She said the boys recreated photos from their childhood.

Sylvia said in a way she’s still recreating memories of Robert after his death. That’s why she keeps a voicemail from him on her phone.

“Hey Mom. This is Robert. Just wanted to catch you. I wanted to wish you a happy birthday. In case you think I’ve forgotten about you. I think about you guys everyday. I’ll catch up with you later then I guess. Talk to you later. Buh bye.”

Sylvia said that some days are harder than others. She says she’s still learning to live with the grief of losing a child.

“I’m having a little bit better success in remembering a few things about Robert and smiling about them because I want to remember,” Sylvia said. “I don’t want to forget anything.”

Sylvia said for his family and friends, that means remembering the man with the gentle spirit and the kind heart.

Robert Henry’s tombstone reads: “Beloved Son, Brother and Protector.”

Robert Henry’s tombstone in Virginia. Photo courtesy Sylvia Henry

If you or someone you know is depressed or thinking about suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. Or you can text the Crisis Text Line at 741741. Both are available, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Correction: The original version of this story said that Joe Donadio was accused of harassment-he was not accused of physical assault but only of being a “threat to himself and the people around him.” This story has been updated to include comments from TSA after initial publication.