Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Shots Fired chapter 1

By Brendan Byrne

Around 2 a.m. on Sunday, June 12th, Latin Night was wrapping up at Pulse nightclub in Orlando. After a night of partying and dancing, about 300 people were paying their tabs as bartenders ended the night with “last call.” The music was loud, the club was dark and it was small.

Outside, 29-year-old Omar Mateen pulled up to the club. Armed with a semi-automatic assault rifle and pistol, he entered the club.

Then, he started shooting people.

Timeline

The following timeline is based on documents, 911 calls and body camera footage released by the city of Orlando and other responding law enforcement agencies, interviews with law enforcement officers and firsthand accounts from witnesses that were inside the club.

The audio in this story may be graphic to some listeners. Discretion is advised.

Shots Fired

Detective Adam Gruler is working the club that night as extra-duty security. At 2:02 a.m., the first shots ring out and he calls for a Signal 43: officer needs help.

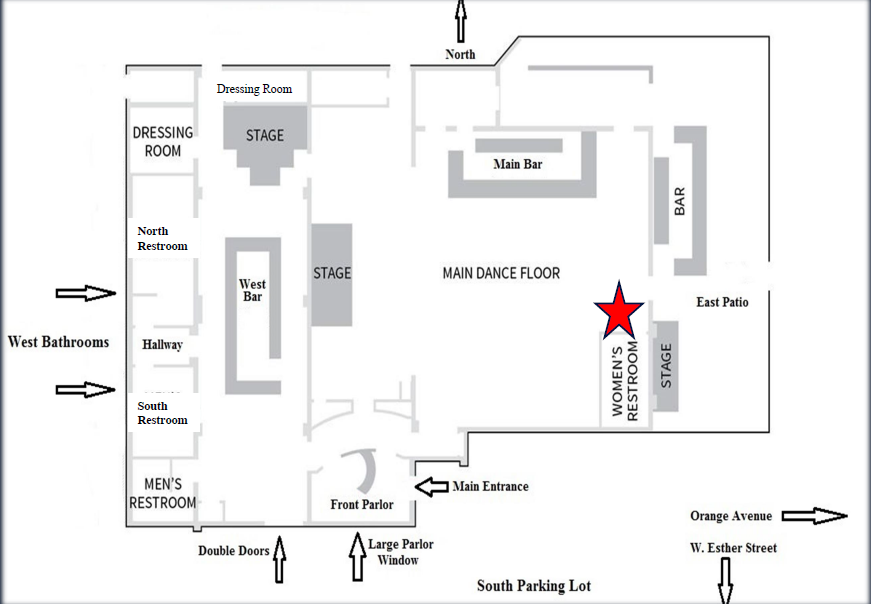

Victims inside the club flee in multiple directions. To the patio to the east, out a back door north and some head to the west bathrooms. Gruler fires several rounds at the suspect, who was standing just inside the double doors. Gruler is outside the club, firing inside, about a minute after those first shots. That’s when the first wave of law enforcement arrives.

At 2:05 a.m., there’s a pause in the gunfire. Then, a team of four officers, including Gruler, make their entrance into the club. Omar Mateen, the gunman, moves from the main dance floor to the bathrooms, on the west end of the club.

At 2:08 a.m., another team of law enforcement agents enter the club from the east patio and begin rescuing victims from the dance floor.

“It’s not a very big club. A lot of water, there were mirrors on the wall, so that kind of messes with your depth perception. It’s dark.” Orlando Police Department SWAT Captain Mark Canty

In the chaos of the situation, first responders were trying to get a handle on what happened, where victims were located, where was the shooter – or if there was more than one shooter.

They relied on calls to 911 and the answering dispatchers to gather as much information as possible to help law enforcement.

In one account, a caller dials 911. Dispatcher Joe Dellova is collecting as much information on the situation as possible, all the while trying to calm the caller. On the line, the caller says his friend is inside the club and can see the shooter. Dellova tries to get a description to tell responding officers.

Reports from 911 dispatchers show the shooting started again. Victims inside the club are calling for help. Some go silent on the line. Others describe their injuries; they’re shot in the arm, shot in the leg. Dispatchers can hear screaming and moaning on the lines in between gunshots, sometimes 20 or 30 shots at a time.

And then, the shooting stops at 2:17 a.m.

More officers enter the main dance floor. There are so many victims lying on the ground, officers ask: “If you’re alive, raise your hand.” They begin pulling victims out.

The SWAT team is called out.

Now, the shooter is with victims inside the bathroom. One hostage contacts 911 dispatchers and says the shooter was reloading his firearm. Because law enforcement couldn’t see the shooter, they didn’t engage, said Orlando Police Chief John Mina.

“Between 2:30 and 3 a.m., our officers and SWAT team were set up in a location where we thought the suspect was, but there’s a lot more that goes on,” Mina said in an interview about ten months after the shooting. “Our officers are basically gathering intel, getting the layout, rescuing the people from the rest of the club.”

SWAT Captain Mark Canty arrives at the scene. “My mind went immediately to the people that were still inside,” he recalls. “So I went to the south double doors to look inside to try and get a picture of how the club was and how we were going to get in there and get those people out and also stop his violence. It’s not a very big club. A lot of water, there were mirrors on the wall, so that kind of messes with your depth perception. It’s dark. So just trying to gather information to see how we’re going to tackle this problem.”

Terrorism In Orlando

The scene quickly evolved from an active shooter to a barricaded gunman with hostages.

Mateen is hiding in one of the bathrooms on the west side of the club. There are two restrooms with a small hallway between them, and doors that lead into that hallway. So if you walk down the corridor, there’s a door on your right – to the north bathroom – and a door on your left – to the south bathroom. Mateen is holed up in the north bathroom, on your right.

At 2:35 a.m., the scene takes another turn: Terrorism.

Omar Mateen would make three more calls, answered by a crisis negotiator. At around 2:50 a.m, that’s nearly 40 minutes after the first shots, Mateen claims to have bombs in his car. Later, Mateen would say that he has bomb vests, and he would attach them to hostages.

Tactics Change

Canty has been with OPD for 17 years. After Columbine, the SWAT team trained the entire police department, utilizing a brand-new, unoccupied school for training. The team also looked at other events, like the Moscow theater hostage crisis, the shootings and bombings in Mumbai India, the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings, and the theater shooting in Aurora, Colorado. They wanted to try and tailor the training to consider what might happen. Even still, Canty said, this situation was different.

“This call went very rapidly from an active shooter to a barricaded gunman and then to a hostage rescue,” Canty said. “Tactics are completely different, you know, active shooter we’re taught to press the threat and go after the shooter and that’s the best way and the quickest way to eliminate his violent acts and save people. Once you go to a barricaded gunman, we lose some of our advantage because he knows where he’s at, we’re going into an unknown.”

Mateen spoke with 911 and crisis negotiators until about 3:30 a.m., then nothing more from the shooter.

During that time, OPD says victims were rescued from the dance floor. More were rescued from an office above the bar, and even more from a dressing room in the north.

Loss Of Life

At 4:09 a.m., a caller inside the bathroom said Mateen would strap bomb vests to the hostages. By 4:31 a.m., more than two hours after victims ran into the bathrooms only to be taken hostage, they start calling 911. Desperate. Panicking.

It’s during this 4 o’clock hour that law enforcement feared there might be more loss of life if the shooter had bombs, and the decision was made to go after the shooter and rescue the victims.

“The plan was to breach an exterior wall on the south bathroom and rescue as many people as we could before he did anything else violent,” Canty said. “The thing that people probably don’t realize is that the entire time that we’re doing this, preparing this, there’s a team that’s ready if he starts shooting again, there’s a team that’s on standby, immediately, and they know if they hear gunshots, they’re to go.”

Canty briefs the police chief on the explosives and what the situation is like inside the club.

“There’s really only two options: Do we breach the north bathroom and go after the killer, or do we breach the south bathroom and go after more hostages? The chief immediately says we have to save as many people as possible, so we decided to go after the south bathroom. I let my field commander know it’s a go, and let me know when you’re ready.”

At 5:02 a.m., SWAT breaches the wall. There are explosions, but explosion didn’t fully breach the wall . They use a large truck to ram the wall.

Shots fired again. They engage the shooter. At 5:15 a.m. — three hours after the shooting started — Mateen is dead.

Forty nine victims are also dead.

Criticism

In the days and weeks after the Pulse shooting, attention turned to the response of law enforcement.

“Police face questions about delayed response to Orlando shooting,” read a headline from the Los Angeles Times not 24 hours after the incident. Survivor Tiara Parker tells The Washington Post: “They took too damn long.”

Chief Mina said the delay was because the situation turned to a barricaded gunman, and tactics change.

“That’s bullshit,” said Chris Grollnek. He’s an expert in police tactics and served on the SWAT team in McKinney, Texas, and one of the first to publicly criticize the police response.

Nearly a year after Pulse, he remains critical of their response, especially of the idea that around 2:20 a.m., the situation became a barricaded subject situation. “The guy already demonstrated that he had a propensity for violence, that he was going to kill people because he already started. They had text messages that people were bleeding out.”

Grollnek said police training has changed since the Columbine shooting in 1999.

“The No. 1 priority is stopping the shooter,” Grollnek said. “It doesn’t matter if you end up shooting someone on accident, it doesn’t matter as a police officer if you get shot, it doesn’t matter if your partner goes down. You do not stop until you stop the shooter. Period. Full Stop. And that did not happen at the Pulse nightclub.”

Mina continues to stand by his decisions that night. He says because there was no shooting at the time, the situation was not an active shooter. Instead it was a hostage situation, with Mateen having the tactical advantage.

“If you can picture yourself in a 141 square foot bathroom with one entrance, and you’re surrounded by hostages, you know how the officers are going to come in. The advantage is to that suspect and shooter,” Mina said. “Once that door opened, I’m sure he would have opened fire on our officers. Our officers trying to protect lives would have to return fire into that small area, putting the hostages at grave risk.”

The Pulse shooting forced many police agencies across the country to evaluate their training and level of preparedness for a mass shooting incident. Mina and his staff have taken a close look at the response, and have been talking with other law enforcement agencies about best practices and lessons learned.

But Mina said there’s not much to change at the Orlando Police Department in the wake of the shooting.

Most criticism of the OPD stems from the decision to not engage the shooter when he was barricaded in the bathroom, and instead approach it as a hostage situation. Mateen didn’t mention a bomb until 40 minutes after the first shots were fired.

“If officers had gone into those bathrooms, the loss of life would have and could have been even greater,” Mina said. “There was extreme danger to the surviving hostages in those bathrooms if we would have entered earlier.”

Investigation

A year out, and the investigation into the shooting continues. The Florida Department of Law Enforcement conducted an investigation and has sent the finding to the State Attorney’s Office.

The FBI is investigating ballistic evidence and whether any victim was hit with friendly fire. “To this point, there is no indication that any victim was killed from friendly fire, but that part of the investigation is continuing,” Mina said.

“I think the No. 1 thing is you don’t know how you’re going to act until you’re in the field of fire,” Grollnek said. He hesitates to criticize the responding officers, and says it’s bad for others to Monday-morning quarterback their response. “But if you don’t question the leadership, then you’re just as grotesquely negligent as the leadership that night.”

Just days after the shooting, Chief Mina asked the Department of Justice to review the actions of the OPD in what’s called an after-action review, although it’s unclear when that will conclude.

What is clear is that Omar Mateen killed 49 innocent victims that night, injured more than 50 people, and risked the lives of the over 300 local law enforcement officers that showed up that night.

Listen to the audio version of this story by subscribing to the “Life After Pulse” podcast.

Chaos in the ER chapter 2

By Abe Aboraya

Orlando Regional Medical Center, just three blocks from the Pulse nightclub, got 44 victims the morning of June 12. Nine of them died.

Health care workers describe the absolute chaos as victims with multiple gunshot wounds flooded the emergency room. Blood bank workers had to carry bags of blood by hand in buckets to the ER. Nurses had to squeeze blood into people because there weren’t enough pressure bags. At one point, they couldn’t even find a sheet to cover one of the deceased.

And then came the call overhead: Police believed, wrongly, that a second shooter had come to Orlando Regional Medical Center.

With all that happened, the morning of June 12 may have been the hardest shift in the lives of people inside the ER.

Getting To The Hospital, By Any Means Necessary

Officer James Hyland’s black F-150 was used as an ambulance the night of the shooting to bring victims to Orlando Regional Medical Center. (Photo courtesy of Orlando Health)

The Pulse shooting highlights a flaw in the U.S. health care system: The closest hospital gets the most patients in a mass casualty incident.

It’s been documented in research looking at other disasters. And it’s something hospitals have to be prepared for.

“Well, I think you hit the nail on the head,” said Eric Alberts, the director of emergency preparedness for Orlando Health.

Hospitals, Albert said, can no longer think, I’m a general care hospital. I don’t have to worry about events like this.

“Those are excuses really, right? You can’t help where bad things are gonna happen,” Alberts said. “Bad things are happening in the community everywhere. It may be next door, like Pulse was for us, half a mile. That was just a coincidence. We were fortunate we were the Level 1 trauma and we had been trying to get prepared and were there to help care for the patients. But other hospitals are just gonna have to deal with it.”

Forty-four gunshot victims came to Orlando Regional Medical Center that morning. Most of them came in the first hour, and a third of the victims were brought by police, not ambulance. To be clear, other hospitals also got Pulse shooting victims. But Orlando Regional Medical Center got by far the most patients, and the most seriously wounded.

Orlando Regional Medical Center got 36 gunshot victims in 36 minutes. They came by police trucks and cruisers and brought themselves. Officer Joe Imburgio drove a black F-150, used as a makeshift ambulance. He remembers what it was like coming to the hospital.

“Cluelessness. I’m getting goosebumps talking about it.” Imburgio said. “At first, I went the wrong way in the emergency bay because I thought if I came that way it would be easier for them to unload the victims. And they’re like, ‘What are you doing, what are you doing, you’re going the wrong way.’ And I tried to tell them hey, we have a massive situation right down the road, and they couldn’t fathom it. Another couple passes, there was 15 doctors, 20 doctors out there. And they really understood what happened. … So then they started to realize what they were in for.”

With just 32 people working inside the emergency room that morning, that means there could have been more victims than staff before extra hands were called in. It was utter chaos.

Nine patients died the morning of June 12 at Orlando Regional Medical Center. The dead were lined up in the decontamination area outside the trauma bay while health care workers tried to save the ones who could be saved.

There was a moment when ER nurse Libby Brown realized how bad things were.

“We didn’t even have a sheet to cover a patient that was deceased going to be lined up with the other bodies,” Brown said. “So that was one of the times when I was like this is very, very bad.”

That concentration of gunshot victims stressed the hospital to the limit. Resources became stretched.

“We’re just out of resources,” Brown said. “Just seeing nurses standing at the top of the bed squeezing blood products into people. We have level 1 pressure machines that will push blood in faster, we have pressure bags that will help push blood in faster, but obviously those were all being used up, so you just see nurses at the head of the bed just squeezing blood into people.”

During this, the concept of triage came into clear focus. For most people, triage simply means that health care isn’t on a first-come, first-served basis.

But during a situation like Pulse, triage means doing the most good for the most people. And that means you have to stop caring for those who aren’t going to make it.

One patient exemplified this. He came in with multiple gunshot wounds to the chest. They did what’s called a resuscitative thoracotomy at the bedside, an incision between the ribs to open up the patient’s chest. But the bullet had done its damage to his heart, his spine. There was nothing they could do.

“It was just a very intense scene to watch because Dr. (Josh) Corsa worked so hard to try and save him, and he just wasn’t going to live,” said ER nurse Elizabeth Burrows. “So you look over at one point and he’s just agonally breathing.”

And that’s when Dr. Chad Smith, the attending trauma surgeon that night, stepped in and stopped the resuscitation efforts.

“I cannot give them enough credit as far as having the sound mind to systematically stop and triage and assess every patient to figure out what do we do with this patient and do it quickly,” Burrows said. “Dr. Smith was amazing about how well he handled all of that.”

"We didn’t even have a sheet to cover a patient that was deceased going to be lined up with the other bodies. So that was one of the times when I was like this is very, very bad." Libby Brown, ORMC ER nurse

This kind of triage has weighed on many of the health care workers since Pulse, particularly those who had to make those calls in the heat of the moment.

Nine patients died at ORMC. Did medical providers make the right call? The autopsies showed those nine people had catastrophic wounds. And they were fortunate to quickly make it to a Level 1 trauma center, the best place for them to get care. But know this: those nine faces are burned in the minds of the people working that night.

Smith said he’s trained for this kind of triage, but he’s never had to make those calls in real life.

“When you realize that a patient is not going to be able to saved, any care beyond that point is potentially taking resources and physician effort and supplies from another patient you can save,” Smith said. “And so you have to be able to go from doing the maximum amount of things for one person, to using limited resources to save as many people as possible.”

And then things got worse.

False Alarm: Shots Fired At Orlando Regional Medical Center

Police, with guns drawn, went room-to-room at Orlando Regional Medical Center, looking for what they believed was a second shooter. This photo was pulled from police body cam video as officers followed a trail of blood. (Photo courtesy of Orlando Police Department)

No one is exactly sure why it happened, but at 3:19 a.m., the call came out: Shots were fired at Orlando Regional Medical Center.

It was a false alarm. But police believed a second shooter had arrived in the ER as a victim.

Over at Pulse nightclub, Officer James Hyland was standing by his F-150 when the call came over the police radio: Shots fired in the vicinity of Orlando Regional Medical Center. In recently released body cam footage, you can see officers scramble and jump into the bed of the truck. Hyland takes off, nearly leaving people behind still trying to get into the bed of the truck. And in less than 60 seconds, officers with assault weapons drawn converge on the hospital.

They chase someone who’s running from them as they arrive. Then, they begin searching the hospital, following a trail of blood. Eventually, they find one of the victims on the sixth floor, who’s been shot in the foot. They cuff him while he continues to get care.

Meanwhile, while all this is happening, police are telling the health care workers to barricade themselves. In the videos, you see health care workers crossing paths with armed police in the hall.

And they kept working on the patients.

“I mean, yeah, I was thinking I could get shot, but I’m gonna continue to care for these people, I’m gonna do what we can,” said Dr. Chad Smith, trauma surgeon. “I really had thought about it. I thought about, I want to say that happened in maybe half a second, I thought about my wife, I thought about my kids, I thought about God, I thought, well if this is it, this is it, but I’m not gonna leave these people.”

In the trauma bay, Dr. Michael Cheatham told workers to move a portable X-ray machine in front of the doors. It’s a big box weighing hundreds of pounds, with its own motor to move it around.

“And so we pushed those up against the doors to block them, and I said OK, let’s get back to the patients,” Cheatham said.

Smith remembers seeing workers texting their loved ones. He sent a text to his coworkers, telling them to stay out of the ER. He thought he was going to be responsible for them getting shot since he was the one who called them in.

“It seemed quick, and it also seemed slow,” Smith said.

Ultimately, there was no shooter.

“But that still, it doesn’t take away those feelings I think everybody has had,” Smith said. “That is what has been the most difficult I think for most of the team members.”

It took nearly 45 minutes to make sure the entire hospital was clear. At this point, Omar Mateen had told police he had bombs, and that he was planning to strap them to victims. The decision was made to breach Pulse.

“One of our interns that took a patient to the operating room during the code silver. This patient was dying, and she rolled the patient out there and did her job to take the patient to the operating room, thinking she could be shot.” Dr. Chad Smith, trauma surgeon

Police Breach Pulse, And A Second Wave Of Patients To ORMC

Amanda Grau spent three hours trapped inside the bathroom with Omar Mateen before she came to Orlando Regional Medical Center. (Photo by Abe Aboraya, WMFE)

Amanda Grau was shot in the leg and under her arm, bleeding in the bathroom for three hours at Pulse nightclub.

She didn’t know that police were going to use explosives to breach Pulse. But she did know the shooter claimed to have bombs – so she thought it was Mateen when the explosion.

“When we heard the explosion, we started crying again because we thought it was him doing it,” Grau said. “At that point, he kicked open our door again and shot around one last time.”

Grau was part of the second wave of patients brought to Orlando Regional Medical Center, where health care workers were preparing for a second round of victims. At the hospital, Grau got two units of blood and a chest tube because her lung collapsed.

She had been in contact with her family and police while inside club, but after she was rescued, she wasn’t using her phone. Her family was outside the club during the final shootout but didn’t get in to the hospital to see her until the morning.

“I was disoriented because of everything that happened, being shot and rescued and not knowing if I would need surgery or if I was gonna make it,” Grau said. “So they ended up getting my mom first to try and calm me down. I just kept telling her, ‘He’s coming, he’s coming, other people are coming, we’re not safe, we’re not safe. We need to go.’ She kept trying to calm me down and tell me you’re safe, you’re in a hospital, they’re on lockdown.”

One of the SWAT officers was also injured in the shootout with Mateen. Officer James Hyland drove him to the hospital, and another officer showed him Officer Michael Napolitano’s helmet.

“My reaction was just blank. In my head it’s registering as ‘Holy crap, that’s bad.’ There’s just the bullet hole right in the middle,” Hyland said.

This photo, shared on social media by Orlando Police Department, shows SWAT Officer Michael Napolitano’s Kevlar helmet, hit by one of Omar Mateen’s bullets. (Photo courtesy Orlando Police Department)

Napolitano is fine. He escaped with just some cuts and bruises. The second round of patients was much smaller than the first – just six patients. All of them made it. But back in the club, there were 49 dead.

That led to another problem at the hospital: Hundreds of friends and family showed up, desperate for news of their loved ones.

But What About Mine?

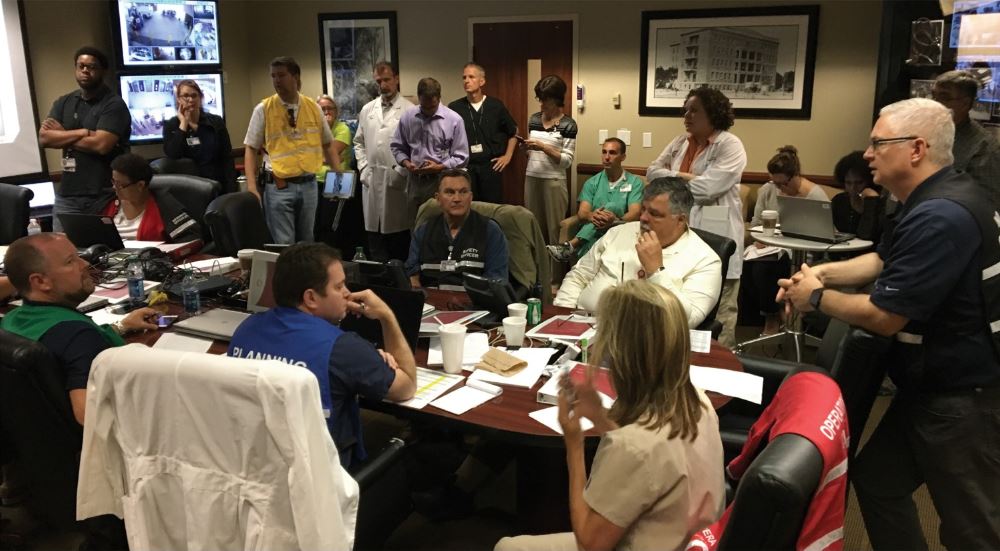

Orlando Health administrators in the Hospital Incident Command decided to bring family members into the hospital while they worked to identify victims. (Photo courtesy Orlando Health)

People desperate to find their loved ones couldn’t get to Pulse nightclub because of the police roadblocks. They could get to Orlando Regional Medical Center, and hundreds gathered, desperate for news.

Holly Stuart is the director of patient experience for Orlando Health. That means it’s her job to make a stay at the hospital more pleasant – a difficult job normally, but an impossible task June 12. When she got to the hospital that morning, she saw two unusual things. A crowd of hundreds of people waiting outside the hospital. And inside?

“I walked by the front desk, where normally we would have a guest service team member managing it,” Stuart said. “And there was a law enforcement officer I didn’t recognize, and he was dressed in SWAT gear. And he had a really intimidating looking machine gun. I don’t know guns well, but it was not the typical thing you see in the hospital. And so I knew right then it was gonna be an unusual day.”

Hospital administrators decided to bring the family members into a big conference room. There were issues, though. There weren’t enough people who spoke Spanish to translate for families. People were fainting and needed medical attention. Stuart said the room was tense.

“People have been woken up in the middle of the night,” Stuart said. “Some people had been at the club, so they’re in a variety of dress. Some people had taken off their shirts to make tourniquets and things like that. So it was an unusual looking crowd.”

To help identify patients, they put Amy DeYoung’s email address up and asked families to email photos and identifying information. She began printing them out and trying to identify people who were dead or on breathing machines.

“I felt like any second that I stop and I don’t print these and take them to the cops is another minute this person is in total anguish,” DeYoung said. “I could hear the screaming, the blood-curdling screaming, every time they would pull someone into another room next to my office and tell them they were dead. You just never forget that sound, it’s horrible.”

At 11 a.m., hospital employees started telling families the identities of those inside. Dr. Joseph Ibrahim, one of the trauma surgeons, stood in front of the crowd in the room and began reading the names and conditions.

Frederick Johnson, stable. Felipe Sanchez, critical. Michael Morales, stable. As they read the names, people called out, or started crying. Phones ring nonstop.

They told the families that if a loved one is at Florida Hospital, go this corner. If a loved one is in critical condition, go to this corner. Stable, this corner. And when they finished, there was a huge group of families still standing in the middle of the room, with nowhere to go.

“And I think that’s when it hit everyone, how many people we were dealing with that were gonna be getting really, really bad news,” Stuart said. “We let them know that we still had several to identify. In the back of my mind, I knew that we only had four. But we still probably had 100 people in the room. You could see them kinda start processing the reality of it. OK, it’s been six or seven hours. They’ve read the list of who they know they have, I haven’t heard from my person. I can remember them staring back at us, like what about mine?”

What Pulse Changed, And What Pulse Can Teach

More than 1,200 volunteer victims drilled for a possible dirty bomb in Orange County. (Photo by Albert Harris, Orange County)

Forty-four victims came to Orlando Regional Medical Center June 12. Thirty-six came in the first 36 minutes. Nine of them died.

There were 28 surgeries done in the first 24 hours. More than 17,000 surgical supplies were used. By the time the last patient was discharged 86 days later, 550 units of blood were given. That’s the equivalent of all the blood in 45 to 55 people.

So what lessons can be learned from inside the ER during the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history? What has it changed? How has it changed the people?

On the day I spoke with Eric Alberts, the director of emergency preparedness at Orlando Health, he had a binder with him. A thick binder, two to three inches at least.

“Well the binder is actually what we’ve learned since Pulse,” Alberts said. “It includes personal notes, it includes our after action report, our corrective actions, it includes our power point we show to other hospital organizations and community partners across the world and the United States. So this is like the playbook, if you will, of what we learned from this situation.”

And it’s possible that the first responder community is taking training drills more seriously after the shooting. This year’s exercise, where they simulated multiple dirty bombs being set off at the same time, was the largest training drill in Florida’s history. More than 1,200 people volunteered as victims.

Visitors to Orlando Regional Medical Center can see how Pulse has changed the hospital.

Since June 12, visitors must walk through security checkpoints with metal detectors to get inside. Now, at the hospital’s blood bank, they know that if there’s a mass casualty incident, they immediately start thawing plasma and universal donor blood.

The hospital is working on a website where people can upload photos and identifying information of people they believe are in the hospital. That way, it doesn’t all come to one email address, and can be accessed by people outside the hospital.

Pulse also changed the people working at the hospital. Amy DeYoung, who worked the day of the shooting to try and identify patients, says she’s more vocal now about her status in the LGBTQ community.

“I just don’t feel it’s my right anymore to stand back and not admit it if someone wants to ask,” DeYoung said. “Or is to say, ‘Oh, you’re married, what’s his name?’ No. Her name, it’s Carla, it’s my wife. I don’t feel like I have the right to lie anymore. That’s the biggest thing.”

Motives Chapter 3

By Renata Sago & Talia Blake

A Man of Contradictions

Omar Mateen prays calmly in one of his first phone calls to 911 on the night of the shooting.

“I want to let you I’m in Orlando, and I did the shooting,” he said.

A series of phone calls continued throughout that night. Based on their content, news unfolded quickly about what his motives may have been—terrorism, mental illness, homophobia, scorned love. These motives addressed Mateen as a political statement, a receptacle for unanswered questions and the object of social commentary.

The Mind Of A Mass Shooter

Mary Ellen O’Toole has spent her whole career of trying to understand what difference that can make. She is a former FBI agent who worked in the agency’s Behavioral Analysis Unit. In the 1990s, she began studying mass shootings and the minds behind them—the Columbine High School massacre, the 2002 Olympic bombings and the Zodiac killer murders.

In this interview with Talia Blake, O’Toole lays the groundwork for understanding the complexities of minds that have committed large scale violent crimes.

The Radical Islamic Terrorism Motive

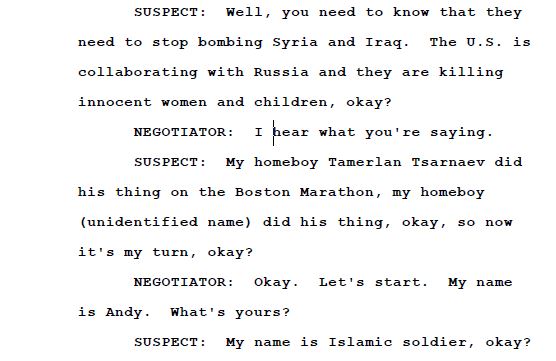

The most immediate indicator, for the public at least, of Mateen’s possible motive is a series of phone calls released by the Orlando Police Department between Mateen and a hostage negotiator named Andy. Here’s part of the transcript from one phone call in which Mateen offers some insight into what message he wants known that night.

Mateen asks Andy if he knows that it is the holy month of Ramadan, a time of fasting and prayer. Mateen says he had had done both the whole day.

Ramadan. Islam. Terrorism on U.S. soil — that became the narrative of Mateen’s motives in the hours, days and weeks after the shooting. That narrative came from lawmakers, media, and average Janes and Joes. Then FBI-director James Comey said at a press conference, “There are strong indications of radicalization by this killer and of potential inspiration by foreign terrorist organizations. We are spending a tremendous amount of time trying to understand every moment of that killer’s path.”

Florida’s Governor Rick Scott continued the post 9/11 mantra of “See something, say something.” At a press conference honoring the volunteers who came to the aid of families after the shooting, he said, “The enemy here is radical Islam. We have to think about how we’re going to stop ISIS. How we’re going to stop the spread of radical Islam. Part of it is, if you see something, you gotta say something. You gotta let law enforcement know. If you see anything happening in your neighborhood that you’ve got questions, call them and let them know.”

Gun victims’ rights advocates called for a special legislative session to discuss guns, and how guns ended up in the hands of Mateen. At the state level, there were protests, and federally, a sit-in on the floor of Congress. But Republican lawmakers and gun rights advocates did not budge. Terrorism. Radical Islamic terrorism.

During a campaign stop for his Senate race just one block from Pulse, U.S. Senator Marco Rubio of Florida was confronted by a gay protester who had lost friends during the Virginia Tech shooting and Pulse. “I don’t feel like you’re doing anything to support the queer Latinos and people of color who’ve been devastated by this,” the protester said.

And Rubio’s response: “Quite frankly, I respect all people. What happened in Pulse was a terrorist attack.”

This politicization of Mateen’s acts by the FBI and lawmakers as terror against the U.S. comes as no surprise to Michael German, who was part of the FBI for 16 years. He went undercover among white supremacists and right-wing militants. These days he’s in New York, behind a desk mostly. He warns about the dangers of reducing Mateen’s motives to radical Islamic terrorism. For him, there is more to the story that has everything to do with politics, power, history and context.

Listen to an interview with Michael German.

Gay rights activists argue that the radical Islamic terrorism motive does not focus on what they feel was a targeted hate crime against gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transgender people. And that, they say, is also political.

“He went into a gay club,” said Orlando commissioner Patty Sheehan, who is part of the LGBTQ community and active in it. “He didn’t go into, you know, any other club in this city. He was looking at other gay clubs, so clearly it was a hate crime to me. People who want to think it’s a radical Islamic terrorism and go no further are people who don’t want examine their own heart and their own hatred towards the LGBTQ community.”

Questions About Mateen’s Mental Condition

In March 2017, more than two dozen victims and their families filed a lawsuit against the people who they say are responsible for putting a gun in Omar Mateen’s hands that led to the shooting: His former employer G4S.

The private global security firm falsified psychological records for Mateen and 1,300 other employees. That got them gun permits. The shooting unearthed this information, which led to a hefty fine against the company by the Florida Department of Agriculture for $151,000 — the largest in the state agency’s history. It also revealed more unanswered questions about Mateen’s psychological state in the moments, months and years before the shooting.

In interview outside her home in Colorado, Mateen’s ex-wife Sitora Yusufiy said he was not stable during their marriage.

“In the beginning, he was a normal being that cared about family, loved to joke, loved to have fun,” Yusufiy said. “But then a few months after we married, I saw his instability. I saw that he was bipolar, and that he would get mad out of nowhere. That’s when I started worrying about my safety and then, after a few months, he started abusing me physically and very often.”

She went on to reason that it was emotional instability and sickness that drove him to go into the nightclub. She said she was unaware of whether Mateen was ever diagnosed with any mental illness.

“He may have had a mental illness that may have went perhaps undiagnosed,” said Nayeli Chavez, a professor at The Chicago School of Professional Psychology. “I mean, I don’t know that for a fact, but that he perhaps didn’t receive adequate treatment, and I think that’s a really important piece.”

WMFE could not obtain any documentation supporting or denying that. But what we do have is evidence that Mateen had made threats to coworkers. But before then, he’d been harassed by his colleagues and superiors for being Muslim. These are some of the statements from written testimony Mateen gave to his employer G4S during the FBI investigation in 2013; statements he said coworkers made to him:

“You guys had your Arab Spring, and now it’s time for our redneck spring.”

“Muslims are similar to Jews. They rape the system and monopolize.”

“We need to kill all the fucking Muslims because of the September 11, 2001 terror attacks on the World Trade Center.”

“You Muslims are the only people who blow themselves up and sing Allahu akbar and think you’ll get paradise for that.”

The list goes on. Arabs sleeping with goats. Riding magic carpets. Being specialists at making bombs. In one testimony, a coworker claimed Mateen looked like a man he’d shot while in the military in Iraq.

According to Mateen, the harassment dates back to when he first started at G4S in 2011.

In an email statement, G4S said it deferred its investigation of workplace harassment to the St. Lucie County Sheriff’s Office — its customer — since employees there were allegedly involved. In an email response, the sheriff’s office said it did not look into the complaints.

The FBI dismissed the investigation against Mateen for threats he made as a sort of tit for tat situation between him and his coworkers.

But the insults continued.

Psychologist Hector Adames, who teaches at The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, describes these insults as microaggressions or paper cuts.

“One paper cut might not impact the person so much, although it might sting when you cut the paper cut. So the idea behind microaggression is that people who are historically oppressed, they received these multiple and multiple and hundreds of little paper cuts throughout their life and that impacts their level of stress. So imagine having billions of paper cuts all over your body,” he said.

In this interview, Professors Adames and Chavez explain how papercuts are symptoms of social disease, and that without proper social support, someone with lots of paper cuts can be triggered to act violently.

Sexual Identity in Conflict, In Question

There are many shades to Mateen. And the last one — the most unsubstantiated — is his sexuality. In an exclusive interview with Univision shortly after the shooting, one man claimed he was Mateen’s lover. Others said he visited Pulse from time to time.

“I don’t think you can have that level of hatred and hanging around a bar, there’s gotta be something conflicting there,” said Orlando Commissioner Patty Sheehan. “It’s just not … people said they’d seen him there before, so clearly he had issues.”

For Ani Zonneveld of Muslims for Progressive Values, an advocacy group, this could be the case because gay Muslims exist, although stigmatized by stricter forms of Islam.

We are left with many unanswered questions. What is certain is that Omar Mateen was a man in conflict in a society filled with conflicting ideas about who he was. Maybe that is the takeaway.

The Burden of Pulse chapter 4.

By Renata Sago

What effects did the Pulse nightclub shooting have on the lives of those who were intimately involved in the tragedy? And those not involved at all?

Keeping A Brother’s Legacy Alive

Women with wet hair exchanged chitchat with each other inside D’Magazine, an intimate and upbeat salon in Kissimmee. Laughter echoed in the background along with the sound of bachata leaping from speakers overhead. On the walls were large posters of modelesque figures with perfect hair and makeup. “These are all clients,” said Jessica Silva, who manages the studio. She walked me past the front desk, past a sign that reads “Love Always Wins,” towards a picture. It was of her only brother Juan Rivera and his partner, Luis Conde.

Then, she pointed to a chair.

“Everything that is in that chair belonged to him,” she said. “That is his chair, his mirror, and you’re going to see both of them, as always … and everything else is from the regional salon.”

Her voice trembled a bit as she pointed to the product line that Rivera, whom she affectionately called Pablo, and Luis had launched together: moisturizer, lipstick that lasts more than 48 hours, and clients; a rolodex deep. This was their legacy.

“My brother is the one that put all the ideas,” she said. “When he decided to do something, he didn’t think it twice. He decided to open this, to do his own line. And Conde’s the one that will put all the sparkles — let’s do it here and we’re going to do it this way, and this is going to be awesome and everything’s going to be like, let’s buy flowers, let’s buy sprinkles, let’s buy whatever it is that has to be there — like, as soon as they knew you, you were part of his family or part of our family.”

Pablo had left Puerto Rico to pursue his lifelong dream of opening the salon. He lived to beautify women. With his mother Angelita as a stylist, he ran the salon for 10 years.

“It was like Juan was working on the left side and my mom was working to the right side,” said Silva. “She was looking to her back and he was there.”

Silva and her mother lost Juan, Luis, and three close friends in the nightclub shooting. For them, reopening the salon at a new location was important in order to keep Juan and Luis’ memories alive. They reopened the studio in December 2016 with help from a cousin, who left her own salon in Puerto Rico to come to central Florida, and three other stylists.

“I personally was ready to do it after two weeks because, for Juan,” said Silva. “No one gave him anything, so everything you see here is hard work, and for people to let them know, that it doesn’t matter how difficult is what you’re going through, never stop doing what you love. In my case, this wasn’t my dream. This is my brother’s dream, so I’m not stopping.”

This is therapy for Silva. It has added to the counseling that she and her two sons receive regularly. She has unplugged her television and limits her social media intake.

And she talks to Juan everyday. She tells him everything.

“I fight with him,” she told me. “I cry, and I explain to him everything that I’m feeling and every month on the 12th, it’s the same feeling. Every Sunday is the worst day of the week—even if I don’t wanna think about it, it’s just like every Sunday I wake up crying and hoping he will come home.”

When Silva talks about her brother, she uses present tense. For her, this salon has been their connection.

“I have a door for each of them. I have a door for Juan and I have a door for Conde. And I can’t imagine that they’re not going to come in.”

Healing The Wounds

These are the kinds of emotions Olga Molina, professor of social work at the University of Central Florida, talked through with survivors of the shooting in the weeks after Pulse. Feelings of loss. Of guilt. Of fear. Molina was part of the first major effort to bring mental health services to survivors and their families through Hispanic Family Counseling, a mental health agency in Orlando. For years the staff there have been providing services to central Florida’s Spanish-speaking community. The executive director came to a meeting at the University of Central Florida.

“She came to tell us that she was getting hundreds of calls a day, hundreds of emails a day. Lots of new clients coming in who were either families of the victims or the survivors themselves and they were flooded with this amount of work, but they really were lacking bilingual, bicultural social workers,” said Molina.

This need, Molina added, comes from the idea that specialists who speak the language and understand the culture and customs of a certain ethnic group can help them identify certain illnesses and disorders that may manifest themselves uniquely based on those cultural practices.

Molina developed a Spanish-speaking group with six members who each identified as either gay, lesbian, or bisexual, and five of whom were undocumented.

“We had a Puerto Rican. We had one Mexican. We had two Venezuelans. We had a Salvadoran and a Guatemalan — and I’m Cuban. So we called ourselves the Latino United Nations,” she laughed.

Despite differences in where they came from, Molina said part of therapy was to emphasize their commonalities and shared experiences as Latinos living in the United States. One commonality she observed were symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

“They were not able to sleep,” she said. “They had nightmares. They had flashbacks. They had headaches, physical symptoms as well as emotional systems that they needed treatment for. One of the first things we did was refer them to psychiatrists.”

Some had not come out and did not want their employers to know, so they lost their jobs and income to take care of daily expenses. And some could not afford medical treatment. All of this has prompted a new research project that Molina is conducting. It looks at the factors that contribute to community resiliency after a mass shooting.

“We’re living in a place here in Florida where there’s not enough long-term mental health services. Incidents like this tell us that we are in great need for long-term services because this symptoms of PTSD do not end in eight weeks. They do not end in two or three months. They can last for years or sometimes a lifetime.”

Seeking Restitution

Berto Cintron-Capo, who lost his younger and closest brother Angel, said regular mental health treatment has grounded him since the shooting. “I don’t honestly know what I would have done without my therapist. She has helped me so much,” he said.

Cintron-Capo was supposed to join his brother at Pulse the night of the shooting, but he decided not to at the last minute. He is the oldest of his siblings and, despite being in deep mourning, has tried to manage his emotions in order to be a support system for the rest of his family.

One way he is working through his pain is through litigation. Several lawsuits sprung up after Pulse, including one against the shooter’s wife and another against Twitter, Facebook and Google for allowing the spread of information that might promote extreme violence. Cintron-Capo and other families of Pulse shooting victims are involved in a lawsuit that holds Omar Mateen’s former employer G4S responsible for getting him a gun permit. News had surfaced after the shooting that the large private security firm had falsified Mateen’s psychological records, and those of 1,300 other employees in order to get them permits.

“We hope to bring money to them in order to replace some of the things they’ve lost in life. Many of them, the ones who’ve survived, have lost their jobs. They’ve got thousands, if not, hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical bills. They need to continue on with their lives,” said lead attorney Antonio Romanucci of Romanucci & Blandin LLC.

He hopes the lawsuit would force lawmakers to consider stricter gun laws. It could yield millions of dollars to the families, a portion of which would go to Cintron-Capo.

“I know for a fact that it’s not going to return my brother,” he told me. “But something’s being done about it. Something needs to be done about it because how could one person have so much power?”

The One Orlando Fund emerged after the shooting and distributed more than $29 million to survivors and victims’ families with the families receiving up to $350,000 each. That money came from donations and experience with past tragedies, including the Sept. 11 terrorist attack.

But for Diana Font, the math just does not add up.

“The distribution of the money, I thought was poorly planned,” Font said.

Font worked was one of the volunteers that rushed to the aid of families like Cintron-Capo’s in the days after the shooting. She worked with members of the Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce at Camping World Stadium in Orlando. Individually, she helped more than 20 families — all with very unique circumstances. Some were estranged, others unaware that their relatives had been at the club that night, or what their sexual orientation had been.

“These were people. These were young people in our society. These were young people. They’re all important,” Font said. “The ones that died are just as important as the ones that are still surviving. Those still need operations to correct things. They’ve got mental issues. They have medical expenses that are still taking place, but you gave the dead more money. And they’re dead. So what did you do? Try to compensate the parent for the child’s death?”

Seeking To Be Understood

On one Friday morning at the Islamic Center of Central Florida, hundreds of men and women knelt in prayer. Kids without shoes ran across the carpet of a large room with Arabic scriptures on the wall, past women in colorful scarves that draped down to their jeans and skirts.

More than 1,200 Muslims attend prayer there each week, and Fatima Rami is one of them. This was the first mosque she came to when she moved to central Florida more than 20 years ago. She has seen the whole physical landscape of the region change and the faces of the people who live here. That includes the growth of the Muslim community.

“Sometimes we have up to 2,000 people attending and there’s not enough room,” she said.

“Things will change, Insh’Allah (God willing),” said Fatima Rami after this service at the Islamic Center of Orlando. (Photo by Renata Sago, WMFE)

There are now more than 50,000 Muslims in central Florida from all over the world, from Bangladesh, Morocco, Pakistan, and India, and many born in the United States. In the hours after the shooting Rami joined other Muslim women to help the victims and their families.

“To be there with the families, to them ‘Hey, I’m here with you, I mourn with you,’” she said. She felt shock when she found out about the shooting. “And then, knowing this was a Muslim, I’m like ‘Oh my God, why is this happening? I mean, why? I felt sorry for myself being a Muslim, and I know the backlash that is coming,” she added.

Security was increased immediately at mosques in Orlando and across Florida due to fears of attacks against Muslims. And those proved to happen. There was reported vandalism of a mosque the day after the shooting in Sanford, a suburb of Orlando. Verbal and physical assaults against Muslims in Florida and across the United States continued in the months after. In early 2017, a fire was started in a mosque outside of Tampa.

For Rami, the fear and judgment have been palpable.

“Myself, many people in my community and my children — because my daughter, also, she wears the scarf — been verbally abused,” Rami said. “What have people said? Just like ‘Hey, go home. Hey, you’re not welcome. Hey, you’re a terrorist.’ My kids have been called terrorist at school, you know? From their friends. Been bullied at school. That’s another issue we have with Muslim children in different schools.”

One month after the Pulse nightclub shooting, central Florida’s Muslims gathered across from Orlando City Hall for a peaceful demonstration in which they condemned violence in the name of Islam. I remember being there with the crowd and seeing women in hijabs carrying signs that said American Muslims for Peace. Several leaders spoke — many non-Muslim, some Jewish, others, Latino and gay, all standing in solidarity with the community.

Muslims from across central Florida gathered one month after the shooting to condemn hatred and violence in the United States and abroad. (Photo by Renata Sago, WMFE)

Imam Hafiz Tariq of the Islamic Society of Central Florida was there.

“The issues that Muslims are facing in different Muslim countries, I don’t think that Islam is the problem. It’s not Islam that is a problem. It’s the political issues that are shaping it up,” he said.

Tariq preferred not to speak about his views on homosexuality. But what he did talk about is the solidarity within the non-Muslim faith community that he’s observed after Pulse.

“They came to sympathize with us and make us feel comfortable that, you know, they’re not going to hold us responsible for what happened in the Pulse shooting, so that was nice,” he noted.

Sympathy has been a focus, but so is getting lawmakers to create policies that protect American Muslims. Florida’s Council of American Islamic Relations is spearheading those efforts. In the past five years, the state affiliate for the Council on American Islamic Relation has grown exponentially in staff and support. It has opened offices across the state and offers free legal services to victims of hate crimes.

I spoke with executive director Hassan Shibly during his recent trip to Washington D.C., where he and a delegation of 400 members of the American Muslim community were lobbying members of Congress to support legislation against a Muslim ban or registry. Shibly explained that his job is part reactionary, and part spreading awareness about the many shades of Islam.

“Unfortunately, the problem is, a lot of people do tend to see the Muslim community as monolithic. And that’s frankly wrong,” he said. “I think nobody has a monopoly on what it means to be an American Muslim, and what’s beautiful is that, you know one of the facts that I’m very proud of is that the American Muslim community is the most racially diverse community and Islam, itself, embraces that kind of diversity. Islam teaches that if you’re racist — if you look down on somebody because of their language or the color of their skin — you’re not just insulting that person, you’re actually insulting God who gifted that person with beauty through their difference.”

But that difference only goes so far within CAIR according to its fellow Muslim critics. The most vocal counter, Muslims for Progressive Values, says the national group is intolerant of differences outside of the heteronormative gender and sexuality framework.

“They’re very orthodox in their representation,” said Ani Zonneveld. Muslims for Progressive Values advocates for equal rights for Muslims based on sexuality and gender.

“We don’t share the same values at all. They claim to represent civil rights, but it depends on what kind of Muslim you are, and they only defend Muslims of a certain stripe,” she added.

Zonneveld said her organization received support after Pulse from other small groups. But the major challenge has been finding ways for the diversity of Islam to have an even larger megaphone.

Exposing The Complexities Of Ethnicity, Gender And Sexuality

Part of what has surfaced within the LGBTQ community is similar — the unveiling of the many shades of a group that mainstream society understood as monolithic.

“It’s just so complex and ever evolving in so many ways. So when we think about trying to understand and provide language to the complexities of individuals holding multiple forms of oppressed identities, it’s important to think about intersectionality,” said Hector Adames, professor of at the Chicago School of Psychology. His research explores the overlaps between race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and language.

“Intersectionality is basically the ways in which different structural systems impact the individual — so how does the impact of racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, et cetera, impact individuals. And the beauty and the power of the intersectional framework is that it helps us understand individual who are oppressed from the outside in.”

That was a takeaway after the shooting for larger LGBTQ advocacy groups such as Equality Florida. Hanna Willard, policy director for the organization, spent the first months of 2017 lobbying. Here, she is on a phone call talking about how the group worked with the State Department to help families in Puerto Rico and the challenges of communicating the resources out there.

“Pulse was a real wakeup call for the LGBTQ movement to lift up the voices of people of color and make sure our work is fully inclusive. We realized we needed to be translating our press releases and translating our resources into Spanish and creole and other languages to make sure these resources were accessible,” she said.

Being An Advocate

For Christine Leinonen, who lost her son Andrew and his partner in the shooting, the biggest takeaway has been the need for sweeping changes in federal and state gun laws. She took her message to the televisions of millions of households during the Democratic National Convention in 2016, one month after the shooting sparked demonstrations across the country and a sit-in.

“The weapon that murdered my son fires 30 rounds in one minute. An Orlando city commissioner pointed out the terrible math. One minute for a gun to fire so many shots. Five minutes for a bell to honor so many lives,” she said during her speech.

The effects of the shooting cannot ever be measured. But for those intimately involved and those not, its burden is heavy and its wounds deep. Jessica Silva who lost her brother Pablo said an anniversary, a one year mark since his death, is just another pang to live with.

“I can’t imagine just commemorating or whatever you want to call it on the 12th,” she said in tears. “Three-hundred sixty-five days without hugging him.”

Memorials chapter 5

By Catherine Welch

As the world woke up to the horrible news, memorials started to emerge around Orlando. What happened to the thousands of items left in remembrance? And why do we memorialize tragedy?

Pam Schwartz is the chief curator at the Orange County Regional History Center. She watched the early news reports with a curator’s eye and questions. Who will tell this story? And how?

“To be honest it was me sitting on my couch on Sunday thinking police are investigating, doctors are saving lives,” Schwartz said. “I’m a curator and a public historian, and the role I need to be playing is to preserve this, so that in 150 years nobody gets to forget that it happened. And so I started to craft a five-page plan, which I brought into my boss on Monday. And then that’s just what set the ball rolling.”

While Schwartz was working with city and county government to decide who had permission to collect items and become custodian of the sites, she watched the flowers and notes and posters pile up.

Florida summers are wet and hot. An afternoon shower in 90-degree weather can turn a letter into a baked pile of pulp within hours. So Schwartz took hundreds and hundreds of photographs documenting the raw emotions in those objects left early on.

It was all she could do while her five-page plan snaked its way through the approval process. It took two weeks for the history center to become officially in charge.

Then it was time to work.

Schwartz faced unique conservation issues. The weather created mold and erased writing on poster boards. Moisture oozed its way into laminated photos. Many of those first items left were destroyed.

“You know, I think some of these items just belong to the angels, ” said Schwartz.

So Schwartz’s team started clearing items left at the hospital, Lake Eola and the Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts. The Lake Eola memorial had to be cleared first to make way for the city’s Fourth of July celebration. Then it was on to the performing arts center, where memorial items nearly covered the enormous front lawn.

This was where President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden stopped to lay flowers. Those flowers, Schwartz said, were stolen almost immediately.

One thing that was saved, and saved quickly, was a white Ikea couch covered in messages.

“It’s one of those things where you can ask the question, ‘Why do people give the items they choose to give?’ Somebody left a couch. What? But it’s no, Ikea is known for its furniture, and so what did they have that seemed pristine?” she said.

“There’s a lot of, I suppose, connections you can try to make between the white couch and Pulse,” Schwartz added. “Pulse was known for their white room at a time and their white couches, but really it’s probably just the fact that Ikea does furniture so what do we have, we have this couch and so they took it out there. We don’t know their exact reasons, hopefully we’ll be able to work with them to get that full story. But then from there, people upon people upon people signed it.”

The 49 White Crosses Arrive in Orlando

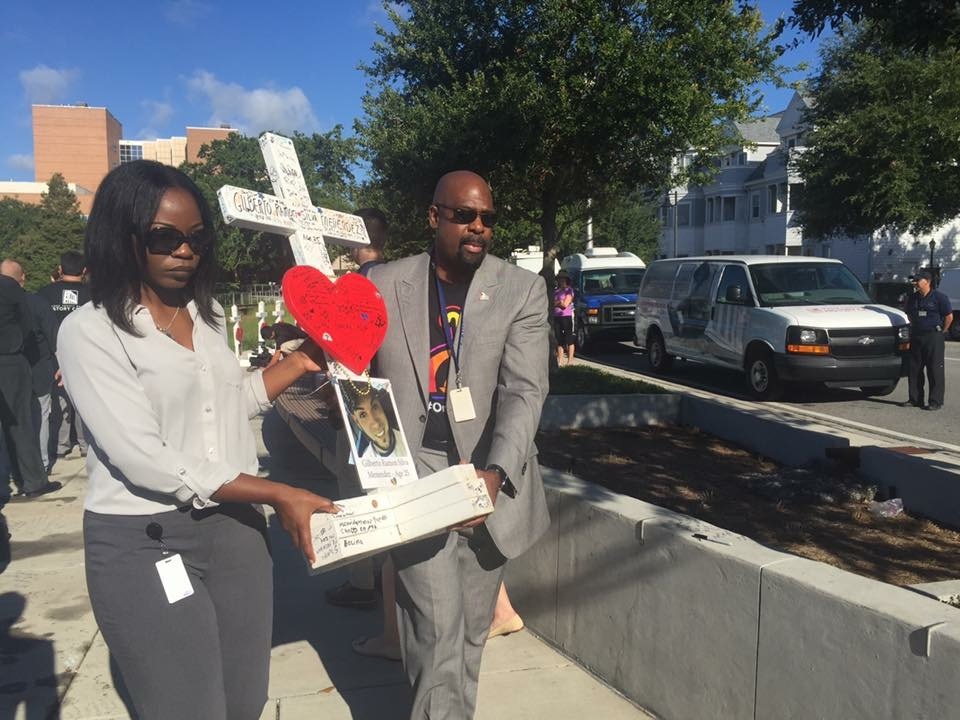

During this first month after the shooting Schwartz’s team was also tending to the memorial at the Orlando Regional Medical Center. This is where Greg Zanis brought his 49 white, wooden crosses. One for each victim.

He started making the crosses 21 years ago as a way to grieve the murder of his father-in-law.

He was in church the morning of June 12th when he heard about the shooting. By the time he got home, there were nine phone messages begging him to bring his crosses to Orlando. Two of those calls were from victims’ families.

So he started work that Sunday afternoon and early Wednesday morning, he drove toward Orlando.

Police escorted him in. Zanis’ plan was to put the crosses at the performing arts center, but a police officer told him no — place them at a park on hospital property.

“He explained it to me a little bit: This is where the wounded are at, this is where they’re being pronounced dead at. And this is [three] blocks away from the Pulse,” Zanis said.

While setting up the white crosses with big red hearts and the names and photos of each victim, people brought Zanis sandwiches. Someone bought him a cellphone, and that night the restaurant wouldn’t let him pay for his dinner.

“Orlando really stepped up and showed love like no other city that I’ve ever been to has ever done before. Just the, I don’t know if you know, I got to meet the governor when he came out and we hugged together and it was just such a wonderful experience from my point of view,” Zanis said.

Over time visitors covered the crosses with hand written messages, letters, candles and objects stacked up around each cross. Then on July 12th they were ceremoniously removed from the hospital park and taken to the Orange County Regional History Center where Pam Schwartz started taking care of them.

Crosses made by Greg Zanis were ceremoniously removed from ORMC on July 12, 2017. (Photo by Catherine Welch, WMFE)

Curators cleaned each cross and the items with it. Then the cross and the items were placed in a box. “So everything that’s with Brenda’s cross, is in Brenda’s box. Everything that was with Corey’s cross, is in Corey’s box,” Schwartz said.

The boxes are actually custom-designed cases with a clear front panel, so the crosses can be both protected and visible.

Greg Zanis is awe struck at the care the history center is taking with them.

Those 49 crosses changed his path, he says. Since Orlando he’s received donations including $10,000 in lumber, and he now works full time making crosses. Right now he’s making hundreds of them for Chicago murder victims. Zanis has set up a nonprofit to help pay for all of this.

He was already well-known, but Orlando just cranked up the spotlight.

But he doesn’t want the fame. He wants people to see him as the same humble guy who made that very first cross 21 years ago.

“That’s a guy doing something that’s not trying to get famous. I’m trying to help these families deal with grief that I’ve been dealing with for 21 years,” Zanis said. “And that somebody cares enough to come over there and put up a cross for them and come over there and hug them.”

And so he continues his work. And Pam Schwartz continues collecting Pulse memorial items.

Her team has collected more than 5,000 items. They also have photographs and oral histories.

And here’s the thing: Nobody planned or budgeted for this massive collection. How could they? The financial costs and man-hours are still unknown since they’re still collecting Pulse items.

When will they stop?

“We don’t know. 9/11 is still collecting. They’re still conducting oral histories. They go to the ICU, men who were saving lives that day and inhaled things into their lungs and are now dying as a result of 9/11,” said Schwartz. “Fifteen years later they’re doing oral histories, and they’re still collecting, things are still coming out. We’re still collecting the Civil War, we’re still collecting ancient Rome.”

‘To me, this is the Embodiment of Love’

Artist Michael Pilato had an immediate response to the shooting. Like Greg Zanis, he uses art as a way to heal from his own tragedy: the death of his daughter.

“To me this is the embodiment of love,” Pilato said. “I’m so happy I’m here.”

He moved into a studio near downtown Orlando, a home away from home, to paint sketches of victims, survivors and those who made a difference. Pilato and his assistant are painting these sketches on huge panels filled with symbols and portraits.

Artist Michael Pilato stands next to his portrait of Amanda Alvear in his Orlando studio. (Photo by Catherine Welch, WMFE)

On one panel, he’s painted Amanda Alvear. She was recording video on Snapchat from the dance floor when shots rang out. Michael has painted her with a shy smile, her black rimmed glasses peeking out from under a blue green hat. She’s standing next to her mother, Mayra Alvear.

“Who’s just an amazing woman,” Pilato said. “She’s helped pull a lot of the families together. She actually went to Puerto Rico, met us in Puerto Rico to help us with translation. We went to some graves in Puerto Rico together, it was very beautiful, and she’s just all about love.”

He’s painted the portraits of survivors, LGBT activists, poets, CNN’s Anderson Cooper, police who were there that night, nurses and children who responded by making hundreds of paper hearts.

These elaborate sketches are for a larger piece called “Inspiration Orlando.” What that is going to look like is yet to be imagined. He envisions a blend of high art and video.

Using Skin and Ink to Memorialize Pulse

Others have memorialized the tragedy in small ways.

“I just have a simple little pulse mark on my ribs,” said Logan Creasman.

Creasman woke up on June 12th and read about the shooting on her Facebook feed. The 22-year-old remembers sitting in church wondering if all her friends were safe.

They were.

Hundreds of people lined up for days outside tattoo parlors that were volunteering to help raise money for victims. Creasman was one of the countless number of people who used flesh and ink to memorialize the shooting. Even though she didn’t know any of the victims, the shooting hit close to home.

She hadn’t fully come out. She had told her mom a few months earlier, but not her dad. He’s a pastor, and she knew how he felt about homosexuality. “So when I was trying to find the time to come out to my dad, when this happened it moved me so much I felt like I had to in a way,” said Creasman. “I felt that it was important that he knew why I was so moved and why it affected me so much.”

So just a few days after the shooting, she told him.

“It was right after the candlelight event at the Dr. Philip’s Center, and we were just walking back to the car and I told him,” said Creasman. “And I could tell that he was kind of hesitant, but I think that he was alright with it. There was a lot of talking after that that I don’t need to get into.”

A year later, she’s glad she got the tattoo. It’s a way to make sure Pulse is never forgotten.

“And it’s a nice reminder of what came from it. Because it felt like after the shooting the community, both Orlando and the LGBT community, came together,” she said. “And even though something really tragic had happened, it still helped create this sense of unity and community, and I wanted to remember that, not just the shooting itself, but what was a result of it.”

What it takes to build a memorial

Like ancient Rome, actual memorials aren’t built in a day. As Schwartz and her team continue to collect and preserve memorial items, plans are just beginning for a permanent memorial in Orlando.

Days after the shooting, reporters started peppering Orlando’s mayor with questions about a permanent memorial. Over and over, his answer was that it would take time. And six months after the shooting it looked like the city would buy the nightclub and start that process. But then the nightclub’s owner decided to take the project on herself and backed out of a deal with the city.

Mount Holyoke College professor Karen Remmler thinks deeply about how tragedies are memorialized. She knows that many people will feel invested in the memorial project because they saw Pulse unfold in the news. Like 9/11, Remmler has found that building a memorial for a tragedy that so many people feel connected to will take a long time and require the input from a lot of people from different communities. And it will invariably involve controversy. Which is okay, she said — the tussle is part of the grieving.

“I remember after 9/11 I went to a huge town hall where there were 5,000 people discussing what should happen at the memorial site. This was in 2005. It was very … we had buttons on our table if we wanted to vote one way or the next, and I think that’s very unwieldy,” she said.

“There will be compromises; some people will not be happy,” Remmler continued. “I think that controversy itself is the process. In some ways, that is the work of mourning. It’s not to put something to rest, but to articulate the differences that some people have in remembering the dead, but in a collective society that allows multiple ways of remembering. That those various ways can very often be incorporated into the memorial process or into the memorial itself.”

One big question: how long should it take to build a Pulse memorial? Right now the goal is to open in 2020, but it may take longer.

“In post-war Germany, it took 30, 40 years before the first series of public holocaust memorials were built,” Remmler said. “I think nowadays the time has shortened, partly because of the visual character that so many people experienced the event.”

Remembering Pulse

The black nightclub sits quietly behind a chain-link fence that’s covered in rainbow-colored murals. Carol Human is one of about a dozen people quietly reading notes left at the fence. “I was looking through the fence over there, and it’s just amazing that so much horror and pain and fear took place there,” Human said.

Yahaira Patino is also visiting for the first time. This is hard for her. She lost two friends in the shooting. Wiping away tears, she takes in the art, flowers and letters. She didn’t expect so much left here. Now she wants to see the nightclub turned into a memorial.

“I think it’s a great idea. It was a huge massacre, it was the biggest one in the country, and it was a hate crime as well,” Patino said. “I think it’s something that shouldn’t be forgotten.”

During the past year, I’d drive by Pulse or stop from time to time to check out the letters and artwork or conduct an interview. Only once has it been empty, and that was in the middle of a recent Tuesday. On most days someone’s here taking it in.

Visitor paying respects at Pulse in March 2017. (Photo by Catherine Welch, WMFE)

There is also a constant flow of items, including big pieces of art, like a massive top hat covered in hand written messages. And nearby, there’s a wooden display box with names and photos of the 49.

Banners, photos, wreaths, letters, flowers and votive candles also flow in and out of here.

Why do we do this, leave items, memorialize?

The people who ponder that question have a few thoughts. It’s a way to mark death. It’s a way to remember life. It’s a way to process grief.

Life After Pulse chapter 6

By Amy Green

Pulse is situated a mile south of downtown Orlando’s high-rises, on a primary artery coursing through the city. Cars whiz by as mourners examine the artwork, candles and flowers left with care on the hot pavement out front. A screen displaying the rainbow-colored murals of local artists hangs from a chain-link fence surrounding the gay nightclub, serving as a happy shroud for the carcass of a building, which is painted black as it always was.

“Life is about happiness and joy and sadness and sorrow, and I think to live a full life, one needs to be present to all of it and not turn our backs to things like this. If we ignore this, it could happen again,” said Jim Marshall, who is visiting from Seattle.

“But if we allow ourselves to experience it, feel the grief, feel the sadness, move into the love, that’s really what it’s all about. Again, love always wins, and that’s the value to me of coming here. I can move through a lot of the sadness and anger and move into that place of love and gratitude and experience this very sacred, hallowed place. It’s a blessing.”

To Marshall the club now is a tomb, and he considers whether it, and the surrounding parking lot with all of its heartfelt memorial items, should be left as they are.

"My daughter's life was taken there, and so many others. And somehow when I visit there it's just like the angels embrace me somehow. I feel their love. You know, it's just a feeling I have." Mayra Alvear, mother of Pulse victim Amanda Alvear

This is the outpouring that inspired Pulse owner Barbara Poma’s plans for a memorial and museum here modeled after ones marking acts of terrorism in New York City and Oklahoma City. I met Poma outside of the club to discuss the details.

Poma established Pulse after her brother died of AIDS, naming it in his memory. She turned down a $2 million offer last year from the city for the club, saying at the time the bid had left her sleepless and she just couldn’t let go.

I arrive as Poma is tidying up the place. She carries a brown bouquet of flowers to a trash bin. She is wearing a sleeveless dress and heels, and at least once during our talk she stops for a photo with a mourner. Her manner is quiet, and perhaps a little uncomfortable with the attention.

“I’ve handed the property and the project over to our families and survivors and everyone here in Orlando and the world,” she says.

After visiting New York City and Oklahoma City earlier this year, Poma established an advisory council and task force of survivors, family members and others touched by the tragedy to oversee the process. Her onePULSE Foundation will fund the effort. She will gather design ideas through an online survey and eventually will solicit bids from a designer.

“We have no idea how long it’s going to take,” she says. “We don’t know if it’s going to be one year or three years or five years. And I think putting a time on it is unrealistic, and it could create unnecessary stress for a lot of people, especially the families. Because since our process is starting within the one-year mark, some people aren’t ready yet.”

"It just gave us comfort knowing that we can do this. It's been done before. It can be done again." Barbara Poma, owner of Pulse

Ken Foote, author of the book, “Shadowed Ground: America’s Landscapes of Violence and Tragedy,” says only within the last generation has there been a need to learn from these acts and honor the dead.

“These memorials for these horrible shootings and so forth are relatively new,” he says. “People seem to think we’ve always done this sort of thing, but the sense of shame that’s often attached to these events in the past made it very difficult for people to mark these events.”

Memorial Effort Forges Ahead, Without the City

Poma surprised everyone when she decided against selling to the city. Her husband Rosario Poma already had signed a contract. Among those most surprised was Mayor Buddy Dyer.

Negotiations had been underway for months, he said. The city’s primary interest was about protecting the property from a development that would have been insensitive, something like a convenience store. But City Commissioner Patty Sheehan believes the deal fell through because of anti-gay sentiment on the part of some commissioners.

“It’s probably better for her to do this as a private foundation because it would have been difficult for the city to work on a memorial if half of the commissioners are opposed to it,” she said.

Commissioner Jim Gray disagrees. He was one of two commissioners who opposed the deal. The other was Tony Ortiz. Gray said he felt the city’s offer was too high. Ortiz did not immediately return a call seeking comment. Dyer also had no comment.

Getting Started

Among the first memorial sites after the Pulse massacre was at the Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts in downtown Orlando. President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden were among those who laid flowers here while the club remained a crime scene, a large area surrounding it closed off to all except authorities.