Podcast: Play in new window | Download

The Orlando Fire Department had been working on a plan to respond to a mass shooting. It had even purchased vests filled with tourniquets and special needles to relieve bleeding in chest. But at the time of the Pulse nightclub shooting, the plan had already sputtered and the vests sat untouched.

This article was produced in partnership with ProPublica as a member of the Local Reporting Network.

“I need the hospital! Please, why does someone not want to help?”

The man’s screams inside the Pulse nightclub pierced the chaos in the minutes after the shooting stopped on June 12, 2016. With the shooter barricaded in a bathroom and victims piled on top of one another, Orlando police commanders began asking the Fire Department for help getting dozens of shooting victims out of the club and to the hospital.

“We need to get these people out,” a command officer said over the police radio.

“We gotta get ‘em out,” another officer responded. “We got him [the shooter] contained in the bathroom. We have several long guns on the bathroom right now.”

A few minutes later, the Orlando Police Department’s dispatch log shows the police formally requested the Fire Department to come into the club. “We’re pulling victims out the front. Have FD come up and help us out with that,” one officer said.

The Orlando Fire Department had been working on a plan for just such a situation for three years. Like many fire departments at the time, Orlando had long relied on a traditional protocol for mass shootings, in which paramedics stayed at a distance until an all-clear was given. The department had tasked Anibal Saez Jr., an assistant chief, with developing a new approach being adopted across the country: Specialized teams of medics, guarded by police officers and wearing specially designed bulletproof vests, would pull out victims before a shooter is caught or killed.

The Orange County Fire Rescue Department began training firefighters to enter dangerous situations in 2013. The county brought bulletproof vests to Pulse nightclub, but on-scene commanders from the Orlando Fire Department declined to use them. (Cassi Alexandra for ProPublica)

After a recommendation from Saez in 2015, the department bought about 20 of the bulletproof vests and helmets. The vests had pouches filled with tourniquets, special needles to relieve bleeding in the chest, and quick-clotting trauma bandages.

None of that equipment was used at Pulse. Emergency medical professionals stayed across the street from the club. And the bulletproof vests filled with life-saving equipment sat at headquarters.

In the three and a half years before the shooting, bureaucratic inertia had taken hold. Emails obtained by WMFE and ProPublica lay out a record of opportunities missed. It’s not clear whether paramedics could have entered and saved lives. But what is clear is Saez’s plan to prepare for such a scenario sat unused, like the vests.

His effort had sputtered and was ultimately abandoned after a new fire chief, Roderick Williams, took over the department in April 2015. Williams named another administrator to finalize and implement the new policy. That administrator declined multiple requests to comment for this story. Saez said he offered to help but never heard back.

“There was a committee that was responsible for the [policy], however, I am not sure whether one was created and approved,” one fire official emailed another on March 30, 2016.

In April 2016, two months before Pulse, Williams emailed his deputy chiefs asking for a progress report: “Update on Active Shooter?”

The only response was an email asking if anyone had responded. No one did.

Ultimately 49 people died during the Pulse attack, one of the worst mass shootings in modern history.

Saez, a 30-year veteran of the Orlando Fire Department, a paramedic and a member of the bomb squad, has been haunted by the possibility that things didn’t have to turn out the way they did. “I wonder sometimes if I should’ve done something else,” he said in an interview.

“In my mind I’m thinking, ‘Man, if I would have had that policy, if I could have got it done, if I could have pushed it, maybe it wouldn’t be 49 dead. … Maybe it would be 40. Maybe it would be 48. Anything but the end result here,’” he said.

A study published this year in the journal Prehospital Emergency Care concluded that 16 of the victims might have lived if they had gotten basic EMS care within 10 minutes and made it to a trauma hospital within an hour, the national standard. That’s nearly one third of victims that died that night.

“Those 16, they had injuries that were, potentially were survivable,” said Dr. Edward Reed Smith, the operational medical director for the Arlington County, Virginia, Fire Department, who reviewed autopsies of those who died with two colleagues. Smith, whose department was one of the first in the country to allow paramedics into violent scenes with a police escort, has reviewed more than a dozen civilian mass shootings using the same criteria. “How would they be survivable? With rapid intervention and treatment of their injuries.”

A separate Justice Department review last year concluded “it would have been reasonable” for paramedics to enter after 20 minutes, a different time frame from the one Smith analyzed.

Orlando’s mayor, as well as the Police and Fire chiefs, dispute that they could have done anything differently. They say it was impossible to know at the time that there was only one shooter at Pulse or that he wouldn’t resume shooting after he barricaded himself in the bathroom. It was also impossible to know whether a bomb threat he later made was real. All of that, they say, would have kept victims from getting care in time.

Williams, the fire chief, said he still believes the inside of Pulse nightclub was a “hot zone,” or a place of direct threat, which would have stopped first responders from going in.

“We’re not prepared to go in hot-zone extraction. That’s just not what we do as a fire department,” Williams said. “It was active fire, active shooting.”

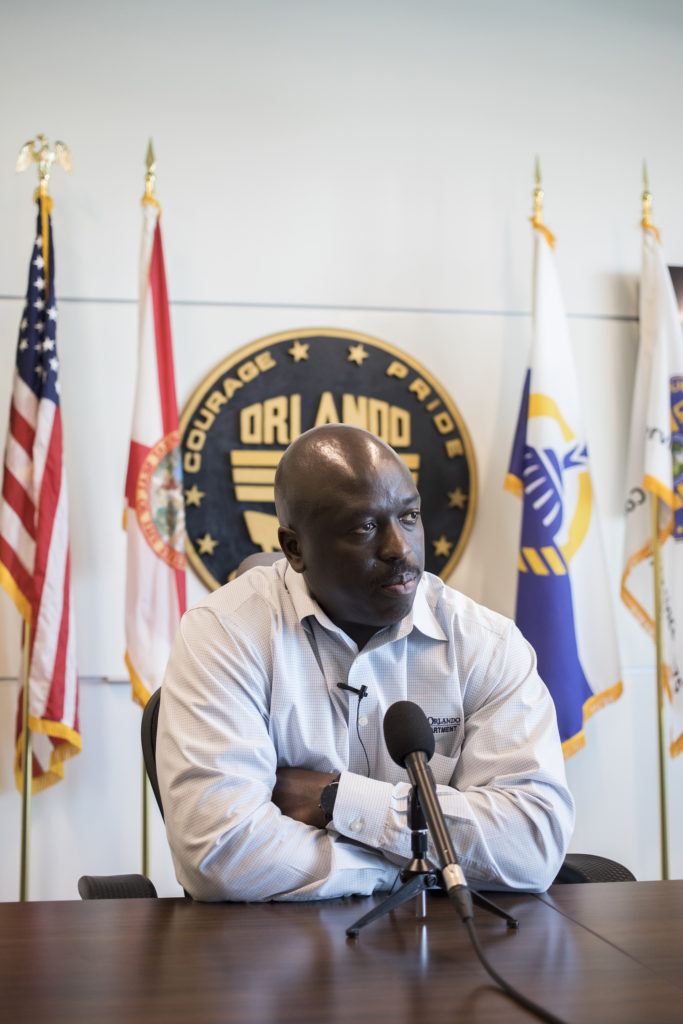

Orlando Fire Chief Roderick Williams says that first responders couldn’t have safely gone in to save Pulse victims while the shooter was still active. (Cassi Alexandra for ProPublica)

But not everyone who responded that night is sure the Fire Department had done all it could. They say some victims might have had a chance had Orlando finished what it started.

Orlando Fire District Chief Bryan Davis was in charge of his agency’s response the night of the Pulse shooting. In an interview, he said his department had done active shooter drills, but it wasn’t enough.

“We didn’t have formalized training,” Davis said. “We didn’t have a policy. We didn’t have a procedure. We had the equipment [bulletproof vests]. But it was locked up in EMS in a storage closet … And unfortunately, we were a day and a dollar too late. ”

“A Wake-Up Call That, for Us, It Can Happen Anywhere”

Just after midnight on March 18, 2013, a former University of Central Florida student pulled a fire alarm in a building that housed 500 students.

He was armed with a rifle, a handgun, hundreds of rounds of ammunition and four Molotov cocktails. Three minutes later, a person in Room 308 called 911: His roommate had pointed a rifle at him.

When police entered the room, the would-be shooter was dead. After his rifle had jammed, he killed himself with his handgun.

Police found handwritten notes about his planned rampage.

“That was a near miss and that was certainly a wake-up call that, for us, it could happen anywhere,” said Orange County Fire Rescue Chief Otto Drozd, whose agency helped respond to the scene. “Everybody is susceptible.”

That year, Orange County, where Orlando is located, started holding department-wide training sessions on how to respond to such situations. It also wrote a new policy that said paramedics, guarded by sheriff’s deputies, should provide aid to victims after a shooting ends, but before a perpetrator is caught or killed.

Also in 2013, the city of Orlando Fire Department assigned Saez, an assistant chief, to create its active shooter policy.

Saez said he began by using the policy adopted by Arlington County as the backbone of his draft but stopped when he learned that another group within the Fire Department also was working on the project. When he tried to merge the two groups together, he was instead told that the other group would handle the policy.

“They were, for lack of a better term, a little gun-shy about how aggressive we were gonna get,” said Saez, who goes by JR, drinking a pint of craft beer through a grey goatee and wearing a Five Finger Death Punch T-shirt. “They started saying ‘Hey, JR’s crazy.’”

Then, in 2015, as the FBI was planning a major drill with public safety agencies, Saez said he was again asked to take the lead on the policy. At the time, Fire Chief John Miller was in the process of retiring and Williams, a longtime veteran of the department, had been named to succeed him.

“The whole active shooter thing, it wasn’t rocket science, it was common sense,” said Saez, who had a reputation for being blunt.

In March, Saez wrote an email to a group of firefighters, including the incoming chief and other high-level administrators as well as medics, “Looks Like I got a Dream Team for this Active Shooter Exercise.” In the email, he laid out a timeline for getting the policy finalized and an active shooter exercise done in April. He said he was choosing which bulletproof vests and equipment to buy and hoped to train the entire department by the end of the year.

But within a month, Williams was sworn in as fire chief and Saez was sent back to work in a fire station. (Such personnel changes are common when a new chief takes over.) The active shooter policy was given to another administrator.

Two months later, the city of Orlando’s emergency manager sent an email to Williams and other members of the Fire Department’s administration calling their attention to a Department of Homeland Security guide for responding to an active shooter. It recommended that fire personnel in bulletproof vests go into “warm zones,” places where victims may be but where a shooter is not believed to be, guarded by the police.

“It echoes our lessons learned and fixes,” the official, Manny Soto, wrote, referring to the Fire Department’s previous active shooter drills, which included practices involving rescue task forces.

In July 2015, the city of Orlando spent $33,000 on about 20 bulletproof vests, according to purchase orders obtained by WMFE. Each vest could hold enough supplies to treat 10 to 15 patients. That was enough for each of the five district chiefs working on any given shift to equip a rescue task force.

The policy was never finished, though, and on June 12, 2016, the night of the Pulse massacre, the Orlando Fire Department policy told paramedics to stay three blocks away if they felt “uncomfortable with the situation.

“To Know That He Could Have Survived Would Be Horrific.”

The “interim” memorial to honor the victims and survivors of the Pulse nightclub massacre seen on Sunday, May 20, 2018. (Cassi Alexandra for ProPublica)

The gunfire started at 2:02 a.m. on Sunday, June 12, just after last call. A request for immediate assistance brought hundreds of officers from 15 police agencies across Central Florida. When the shooting stopped eight minutes later, Officer Brandon Cornwell of the Belle Isle Police Department and three other officers went inside the Pulse nightclub to kill or arrest the shooter.

They entered through a broken window in the front of the club. The club was dark, lit by pink and blue video screens and disco balls. There was no music playing. Unfinished drinks and unpaid bar tabs littered the tables.

As they got farther inside, a woman could be heard screaming over and over again, according to police body camera video of the scene reviewed by WMFE. Sometimes she screamed for help. Sometimes she just screamed.

The scene was so chaotic, police couldn’t figure out who was screaming.

“Who the fuck is this coming from!” one of the officers shouted.

The team walked toward the gunfire and believed it had the shooter cornered in one of the club’s bathrooms. They pointed assault rifles and handguns at the doors and hallways to keep the shooter contained.

Officers then started bringing 14 incapacitated victims out of the club. Victims grabbed police officers’ ankles as they walked by, according to first responder recollections in the Justice Department report.

People — some dead, some alive — fell stacked on top of one another “like matchsticks.” Some victims played dead. Phones rang and rang.

In the ensuing minutes, body camera footage captured the discussion between officers and commanders about getting help.

At 2:23 a.m., a police command officer tried to come up with a way to get paramedics inside. He asked if the shooter’s rounds could get into the main area “if we start bringing FD to try to get some of these guys out of here?”

The officer inside responded: “He’s got a long gun, so yes, can penetrate,” but then said that he was contained in the bathroom and that they had to get the victims out.

A few minutes later, the Orlando Police Department’s dispatch logs show the police asked for the Fire Department “to go in scene secure,” meaning dispatchers were asking the Fire Department to come into the club.

This is about the time the Justice Department concluded a rescue task force could have entered the Pulse nightclub.

Still, the Fire Department did not enter.

Orlando city officials downplayed the significance of the log, saying in a written statement that it only reflected the judgment of a “single officer.”

“In this type of changing situation, this was an isolated perspective and ‘secure’ did not mean the scene was ‘clear,’ which is very important to distinguish,” the statement said. “This was still an active scene with an armed shooter and many unknown threats, like were there additional shooters or were there explosives.

“And in fact, within moments, the suspect made the threat of explosives and pledged allegiance to ISIS. Shortly after this, there were also reports of a second shooting at Orlando Health and the hospital was locked down for approximately an hour.”

At 2:50 a.m., the shooter threatened to blow up a city block with explosives in his car. Around the same time, the Orange County Fire Rescue Department, which had trained with the Sheriff’s Office beginning in 2013, brought 12 ballistic vests to Orlando Fire Department commanders on the scene.

Davis, the Orlando Fire Department district chief in charge of his agency’s response that night, said he told Orange County commanders that city firefighters and paramedics hadn’t been trained on how to use the vests — and wouldn’t use them. Davis’s account was confirmed by an after-action report by the county.

In an interview, Davis said that while his department had done active shooter drills, those hadn’t been enough. In retrospect, he said he wishes he had asked the county firefighters to send a rescue crew into the club.

“When that Orange County chief arrived, I would have looked at him and said, ‘Hey Chief, my guys are not properly trained in the use of those vests. Do you have individuals here that are?’” he said. “And if so, then we utilize those resources that were properly trained … and we assemble them into the rescue task force and move them forward into the scene.”

Orlando Mayor Buddy Dyer said vests or no vests, commanders on the ground would not have told firefighters to go inside Pulse.

“I don’t think that scene was the appropriate place to do it,” Dyer said. “Whether we had the policy strictly or not, I don’t think it affected the outcome at all.”

While paramedics didn’t enter Pulse, some victims who had left the club managed to go back in to help friends.

Jean Carlos Mendez Perez made it outside the club after the shooting, but he realized his boyfriend was still back inside. He went back in to get Luis Daniel Wilson-Leon, who everyone called Dani.

The couple was found by the entrance in the club. Wilson-Leon had wounds to his back, while Perez had wounds to his front. They both died.

“I think (Dani) was protecting Jean,” Laly Santiago-Leon, Dani’s cousin, said.

Laly Santiago-Leon lost her cousin Luis Daniel Wilson-Leon during the Pulse Nightclub Massacre in Orlando, Florida on June 12, 2016. Laly poses for a portrait in Luis’s old room in Rockledge, Florida on Monday, September 17, 2018. (Cassi Alexandra for ProPublica)

Santiago-Leon says it’s heartbreaking to learn that the Fire Department put the policy on the backburner. She said she hopes to never learn who the 16 victims with survivable wounds were.

“I’m still, as I said, I’m still angry that he’s gone,” she said through quiet tears. “But to know that he could have survived would be horrific.”

The Orlando Fire Department’s Leadership Didn’t Show Up During The Attack

Downtown City of Orlando Fire Station One (Cassi Alexandra for ProPublica)

Fire and police agencies from across the Orlando region swarmed to the scene as word of the Pulse shooting spread. Initially, they each responded independently, but sometime in the first hour they established a mobile command center to coordinate their responses. The Orlando Police Department took the lead, but it was joined by two sheriff’s offices, as well as the Florida Department of Law Enforcement and the FBI.

The Orlando Fire Department leadership wasn’t part of it.

According to department protocol, the fire chief was paged at 2:14 a.m. But the Justice Department’s report on how the police responded to Pulse said the fire chief didn’t arrive at the scene until after the shooter was dead. There was no follow-up call to make sure the page was received, the report said.

Williams declined multiple requests to explain why he didn’t show up that night, but city officials have blamed it on a faulty paging system. The policy has changed since Pulse: Now, if the fire chief doesn’t answer a page in three minutes, he or she will get a phone call.

Dyer said he views what happened as a breakdown in communication, not a lack of leadership.

“Operationally, it didn’t affect it,” Dyer said, referring to the Pulse response. “It just would have been better for the morale of the organization if the chief would have been on site.”

Firefighters had their own command system, separate from the Police Department, whose chief was present. The two sister agencies didn’t even operate on the same radio channel, the type of challenge identified more than a decade earlier after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. The Justice Department report said the setup outside Pulse “negatively impacted information and resource sharing, coordination, and overall situational awareness.”

Davis, the firefighter in charge of the department’s response, was four ranks below chief. Looking back, he said, he wishes that he or someone else in his department’s leadership had gone to the police command post.

Williams disputed the notion that being in the command center would have changed the department’s response or prompted officials to send in a rescue crew earlier. In a recent interview with WMFE, he said that training had been in place and that a rescue task force could have gone in if asked for.

“Those commanders on the scene made those choices,” Williams said. “We did exactly what was appropriate based on the resources that was required at the time.

But a month after the Pulse shooting, Williams gave a different response in an interview with WMFE. He said that his department was looking at active shooter protocols and vests, but that “we haven’t trained to that level.”

Smith, operational medical director for the Arlington County Fire Department, said if the Pulse nightclub shooting happened in his community, the response would have been different. With the shooter barricaded in a back bathroom, paramedics and EMTs would have put on ballistic vests and gone inside the club to pull victims out with a police escort.

While conceding that his assessment had the benefit of hindsight, Smith said the story of how Orlando responded to Pulse nightclub isn’t just about the lack of a rescue task force. It’s about the lack of communication between the Orlando Police and Fire departments.

“They had two separate command centers that were, by the way, were on opposite sides of the club” for part of the event, Smith said. “The police commander couldn’t walk outside and walk over to the fire command because they had the club in between the two of them. So there’s no integration there.”

According to Smith’s study of Pulse victims, out of the 16 victims who possibly could have lived, four died at the hospital. That leaves 12 who died either inside the club or in the triage area outside. It’s not possible to know how many of those died on the dance floor, where rescuers could potentially have reached them and provided aid, or inside the bathroom, where the shooter had barricaded himself and held them as hostages. It’s also not clear who would have survived if they had gotten help within 10 minutes of being shot. And for those who could have survived, it’s not clear how debilitating their injuries would have been.

Smith and his team previously studied 12 mass shooting events, including one at a San Diego McDonald’s in 1984 and one at the Washington Navy Yard in 2013. In those 12 incidents, an average of 7 percent of victims died with potentially survivable wounds. According to Smith’s analysis, nearly a third of victims had survivable wounds at Pulse.

Both the fire chief, Williams, and the police chief, John Mina, have a simple response to those who criticize how the Pulse nightclub shooting was handled.

“The fact of the matter is those people weren’t there,” Mina said of Smith and others who criticize the response. “So they can’t say, ‘I would have done this’ or ‘I could have done this’ or ‘I should have done this’ because they weren’t there.”

The city said the Police and Fire departments had nine joint training exercises between 2005 and 2016 on how to respond to an active shooter.

“If we had needed the Fire Department in there, we would have called them,” Mina said. “Many officers were inside the club transporting the wounded directly to the fire department feet away to their triage center.”

Mina later declined to comment further when asked about the dispatch logs showing that the that the police asked for the Fire Department to come to come inside the the nightclub. Dyer described those logs as a “random individual talking about that,” which didn’t reflect the views of police the views of police leadership.

Pulse is no longer the worst mass shooting in the U.S. history. Las Vegas took the mantle last year. Just this year, Florida saw mass shootings at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland and at a video game tournament in Jacksonville.

But Pulse changed the way many law enforcement agencies view the need for a rescue task force. Drozd, the Orange County Fire Rescue chief whose department brought vests to the scene, began working with the National Fire Protection Association to create a blueprint for how police and fire departments should work together to respond to active shooter incidents, which came out this year. He said he hopes fire agencies become more willing to enter “warm zones.”

“That’s where as an industry we can do the most good.”

“I Pray She Made It”

Two weeks after the Pulse nightclub shooting, the upper echelons of the Orlando Fire Department called a meeting. The topic? “Active shooter project discussion.”

Within 10 months, more vests were purchased, and all firefighters had gone through a mandatory 16-hour rescue training course modeled off of the military’s approach to field medicine, reworked for civilians. In April 2017, the mayor stood in front of a fire engine and donned a bulletproof vest with “Fire-Rescue” written in big red letters on the front and “Orlando Fire Department” on the back.

The point of the April 2017 press conference was to show off new equipment the city had purchased to help respond to future disasters like the Pulse shooting. Like the vests that had been sitting in the department’s headquarters on the night of the shooting, the vest Dyer modeled had pouches filled with tourniquets, special needles to relieve bleeding in the chest, and bandages.

Dyer and Williams also unveiled their new rescue task force policy.

“Since Columbine, all these different events happened,” Williams said at the press conference. “We realize a new norm somewhat, but our goal is to make sure our personnel is equipped to handle that new norm.”

Vests provide firefighters with an increased level of protection to ensure they can assess patients & reduce potential injury to themselves. pic.twitter.com/R8zixX9fWA

— Orlando Fire Dept (@OrlandoFireDept) April 7, 2017

Dyer said vests and helmets, which cost about $118,000 would add a layer of protection if firefighters came in the line of fire. The city now has about 150 vests, enough for each firefighter working on a shift to have one.

Those vests could have been helpful in past events, he acknowledged: “Certainly Pulse.”

Neither Williams nor Dyer mentioned the vests and helmets sitting at the agency’s headquarters untouched at the time of the Pulse shooting. Nor did they mention the years of work on an active shooter policy that hadn’t been completed.

The active shooter policy adopted in April 2017 is just two pages long. It says that firefighters working at certain stations will be called into risky situations, operating as a rescue task force, and that all firefighters may be required to do the same.

Ron Glass, president of the union representing the Orlando Fire Department, said the new policy doesn’t have enough details for emergency medical professionals treating patients. He said if another Pulse happens tomorrow, “we’re gonna do the exact same thing again.”

“We have a three-inch notebook … on every type of house fire, every type of specialty, high angle call, below-grade call, extrication call, elevator extrication call,” Glass said. “The only thing that’s not in the book is … active shooters.”

The Justice Department’s Community Oriented Policing Services office, which critiqued the police response to Pulse, has been commissioned by the Fire Department to evaluate its response.

That report is due out soon, and it could give needed closure about the department’s response to the Pulse shooting.

Saez, the assistant chief who had been charged with modernizing the department’s active shooter policy, was not on duty the night of Pulse. But when his wife, who worked for the Orlando Police Department, texted him that the shooting was the “for deal,” Saez remembers driving his hybrid Toyota more than 100 mph to get to the scene.

Saez worked with the arson squad and helped use explosives to breach the outer wall of the club before the shooter was killed. Afterwards, the police dragged a woman to him who had been shot multiple times.

“All I could do was put my hand on her chest to hold pressure and pray, hope, fuck, I hope I did something,” Saez said.

An ambulance finally did come and bring the shooting victim to the hospital. Saez doesn’t know what happened to her.

“I pray she made it,” Saez said.

Saez has filed a hostile work environment complaint with the city of Orlando’s human resources department against his immediate supervisor and the fire chief. The city of Orlando said it is “currently reviewing the facts of this case as it is active and ongoing.”

Saez said he thinks about the Pulse nightclub shooting every day, and feels responsible for not getting the active shooter protocol pushed through. He has a “sick feeling in the gut.”

Correction, October 3, 2018: This story originally misidentified the function of special needles carried in the pouch of bulletproof vests. They relieve air pressure in the chest, not bleeding. It also misidentified the role of Anibal Saez Jr. on the night of the Pulse shooting. He did not work on the explosive breach of the club.

Are you a first responder with PTSD or stress-related symptoms you believe may be related to your work? Do you have a family member or close friend who is a first responder with PTSD or who has committed suicide? We want to hear from you.

Abe Aboraya covers health care for WMFE, an NPR affiliate in Orlando. This year, he is focusing on the toll post-traumatic stress disorder takes on first responders. Email him at wmfe@propublica.org and follow him on Twitter @wmfehealthnerd.